From this day forth

I shall be called a wanderer,

Leaving on a journey

Thus among the early showers

(Bashō, from The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa)

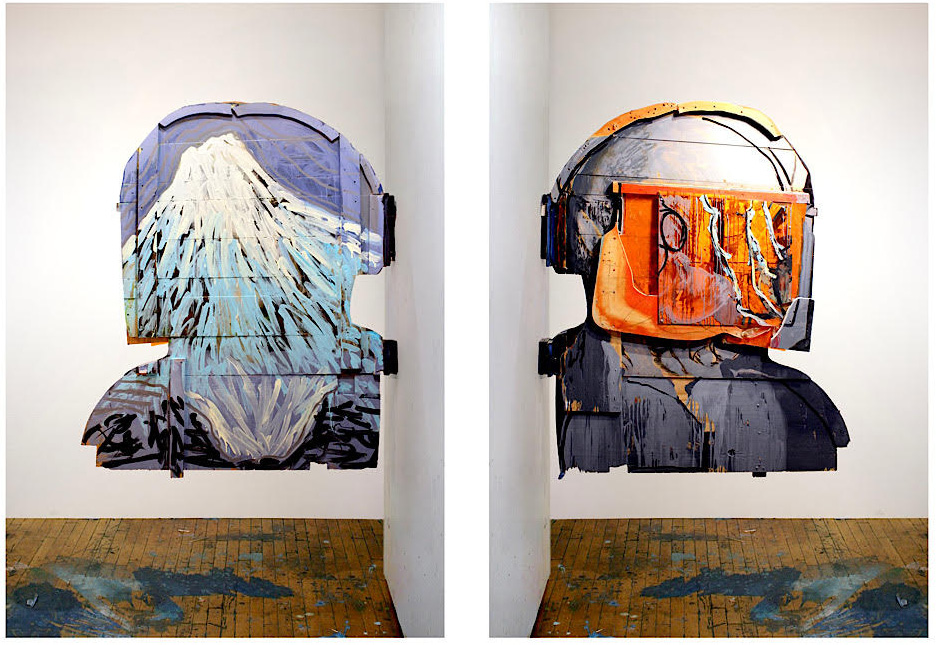

Mount Fuji, Guernica, police helmets, shields, umbrellas: it’s a list of objects that are disparate, some spiritual, others violent and decidedly earthbound, but which only an artist’s path can combine. William Norton is a specific kind of artist who collects ideas and forms, and unites them in strange shimmering and glistening combinations which force contradictory things into close quarters. Contradiction is one of the great advantages of working in the visual arts, where antithetical themes coexist simply by being placed next to each other. Unlike oil and water though, they cannot separate, and so we are forced to consider them together. Rauschenberg championed the art form—placing a ram inside a tire in Monogram (1955-59), and painting the animal as well, and in so doing generating a mythical beast that brought together nature and machine in a most unique way. Norton insists on placing violence and beauty side by side, and the viewer may chafe at seeing holy mount Fuji in the plexiglass visor of a riot gear helmet, but there it is, and what can we do about it?

For one thing, we can learn from it: William Norton’s background explains a lot, and nudges us towards the place from which these ideas emerge. Norton was an army brat, and was raised in Japan, so the dual influences of Japanese culture and military rigor inform the very origins of his personality. Japanese art resides not just in the traditional loci of visual culture such as painting and sculpture, but in a deep aestheticizing sensibility directed at the everyday experience of life passing by—in the arrangement of flowers, the tea ceremony, and even in the inspiration drawn from accident and imperfection—in wabi-sabi and kintsugi. Norton applies this energy to his use of everyday materials as a stratum for art making. He uses ubiquitous materials like plastic sheeting, and found objects, and paints using gold, gold leaf, and radiant blues, postulating that beauty can alight on any form.

The fixation on violence—and mitigating it with beauty—partially emerges from the artist’s youth. The presence of the army as the defining institution of Norton’s childhood, with its hierarchies and its rejection of questioning, clearly triggered the artist to become a determined anti-authoritarian. Still, Chōtarō, the poet quoted by Bashō in the above passage, was a Samurai, and so we see a lyrical version of Norton’s contradiction as a precedent in the idea of a warrior poet.

\What a stroke of luck

It is to see

A picture of Nirvana

In this Holy compound!

(Bashō)

William Norton’s depictions of Mount Fuji are glimpses of Nirvana, appearing on the strangest materials in unexpected circumstances. Norton pairs Fuji with recognizable quotations from Guernica (1937) and thus maintains a balancing

act between a literal evocation of Nirvana—Mount Fuji, and a masterpiece of painting, and a beautiful dystopian hellscape, an inverted Nirvana, Picasso’s Guernica. Like the painted riot gear helmets, the artist confronts us with violence and beauty again, but in this case it is two kinds of beauty: from the placid gentle slopes of the holy mountain, the silhouette of a frantic mother holds up her arms in Changing for Good (2023-24), and in Fujiyama/ Guernica #4 (2023), Picasso’s all-seeing electric light shines unblinkingly next to Mount Fuji.

God of this mountain

May you be kind enough

To show me your face

Among the dawning blossoms?

(Bashō)

An imposing profile projecting from the wall like a hybrid ship’s prow/figurehead or cardboard superhero cardboard cutout, Norton’s series of larger-than-life cop helmets distill his juggling act of symbols into a single representative being. The depictions of helmets are cartoonishly proportioned renderings of actual riot gear helmets—another of the artist’s readymade painting substrates. But the plywood two-sided projections transform the terrifying form of the helmet into a more impressive being than merely a cop. The helmets, while familiar, also have the forms of snail shells, waves, and sundry organic objects. Their coloring of blue and white now begins to meld into the white snows and blue slopes of Fuji. The gold that Norton adds to many of his objects—a reference to the Japanese technique of gilding the background of fans and screens to heighten the presence of the object, adds a comedic grandeur to the helmets that pushes them towards the mythic energy of Bashō’s mountain god. Like so many equivocal figures meant to represent power, order, yet chaos as well, the tumultuous themes in Norton’s contradictory cop beings ultimately negate each other, leaving a gilded enigmatic and uneasy tension that is hard to forget. G&S

Leave a Comment