Imagine an eye exam in which you are not called upon to identify the identifiable —the letter E, the number 6— but you are tasked with trying to see, to make visual sense of, an overwhelming cosmos, your cosmos, the one filled with words written and spoken, images, sounds, planets, minute details and vast expanses, the ordinary, the sublime, that which exists and that which ought to exist. Do this in the context of someone loved and lost, to envision where they may have gone and to know what is left to be seen in their absence and you have as good an idea as I do what Yan Wai Yin’s Localized Blindness may be about.

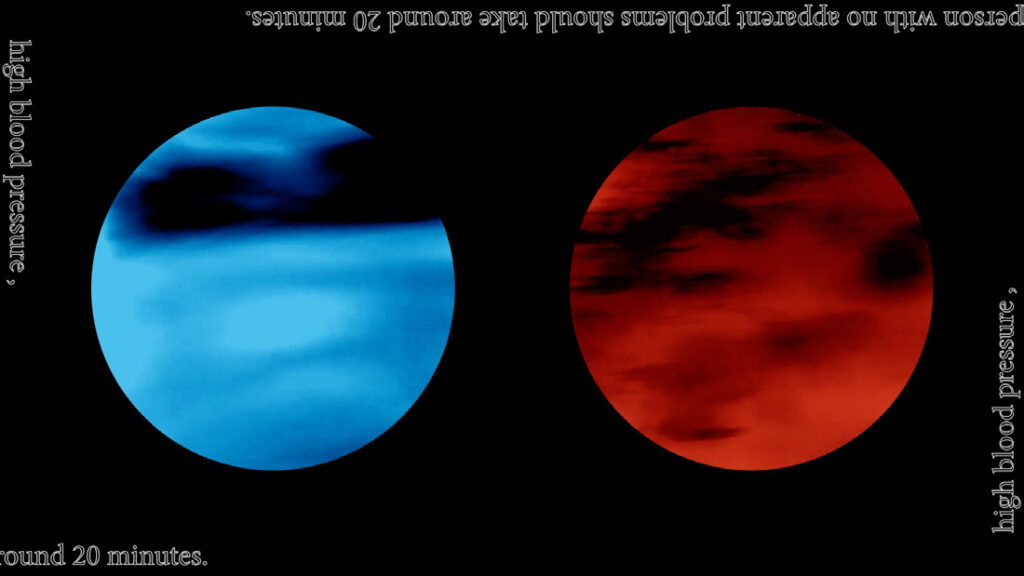

Notes from my first viewing of the film in 2020 read: “This is a mind feast. Beautiful to look at and completely engaging verbally. This is one version of what a film should be.” High praise; and the phrase, “completely engaging verbally,” is quirky enough to warrant tracking down and having another look at this “mind feast.” Re-discovered, the film proved a feast indeed and, like most feasts, presented more to this viewer’s mind than could possibly be consumed in one go. Though only 20 minutes in length, the film manages to assume a symphonic quality with initial themes presented and then varied as if in response to or interaction with myriad sub-themes that compete for the viewer’s attention in the form of images and the forceful interplay of words — Yeats, Foucault, Goethe, Wilde — that scroll across as captions or are spoken over Yan’s artful graphics.

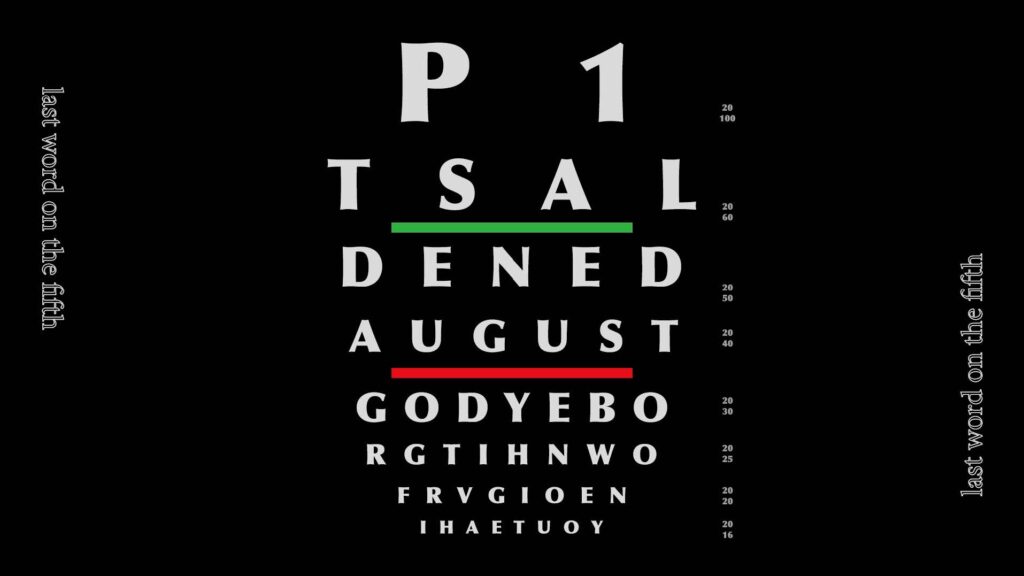

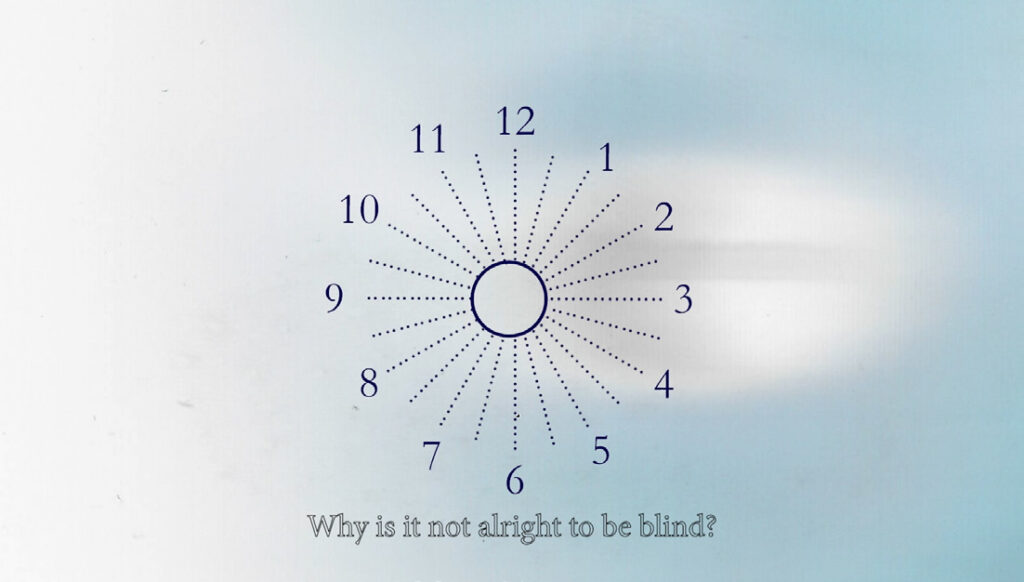

A voice — male, robotic and southern English — sets out at the film’s beginning to conduct an eye exam. “This is an eye test,” it says and briefly proceeds accordingly. But shortly questions and instructions begin to veer. “Can you spot the orange train?” devolves into, “Do you believe your eyes?” or “Why is it not alright to be blind?” “You will be looking at a series of still and moving images,” is followed by the instruction, “Do not open your memory until you have been told to do so.” Here the viewer may be forgiven for wondering if this robot has been calibrated for ophthalmic work alone. But a filmic grammar has been established. Through her film-as-eye-test metaphor, Yan has built a thematic platform upon which her film’s crowded ideation can bubble and roil while putting viewers on alert that their focal powers will be tested.

An eye test is, after all, not one that is passed or failed, not one in which everything must be seen, but a test that establishes what can be seen. One suspects, in fact, that the filmmaker’s intention in making Localized Blindness may not have been to be completely understood but rather to understand herself through a process of externalization. As in an actual eye test where one may be asked to cover one eye and then the other, Yan steers a delicate course between opacity and transparency. Something simmers beneath the surface of this film’s strident pace and sophisticated graphic vocabulary, frames so full of verbal and visual information that the eye darts about the screen trying in vain to absorb it all when, in fact, the point of this informational overload may be to mask something best expressed indirectly.

Watching Localized Blindness one time will tell you that its maker is mercurial, literary, visually skilled, able to identify and expand on unlikely relationships and to express herself eloquently in the medium. But, after more than one viewing, the underlying cri de coeur lurks more obviously just beneath the film’s polished surface. Expressing itself obliquely, subliminally at times, and always at a discreet distance from the viewer is evidence of heartache, loss, longing. Though framed, subdivided and laid out in Yan’s unerring graphic style the film’s photographic images and video clips have a frank, unguarded, homemade look: cell phone shots out of plane, train and high-rise windows; an open suitcase full of clothes, a set of keys with a subtitle that reads, “Goodbye.” A dictionary definition of the word “latency” is edited to suggest an unfulfilled need. A fanciful eye chart’s lines of random letters are in fact scrambled words and phrases. Unscrambling one line reveals the phrase, “I hate you.” A black frame bearing text that reads, “Stay, you are so beautiful,” graces the screen for what might be as much as a half second, arguably not time enough to be read by any but the most competitive eye patient.

So, the notes from 2020 were pretty accurate. Yan Wai Yin’s meticulous, emotionally invested work in Localized Blindness provides more than enough for an inquiring mind to feed on and is, if not “what a film should be,” a telling example of what art as film can be. G&S

This film may be viewed by contacting the filmmaker: yanwywinnie@gmail.com

yanwaiyin.com

Leave a Comment