During the final quarter of the 19th century, while well-heeled Manhattanites were amassing the grand masters of European art—the Rembrandts, the Raphaels, and the Titians—an equally prospering group of Brooklynites began collecting contemporary art produced in France—the Monets, the Corots, and the Cézannes. Thanks to the major donations of art-lovers like Doris Havemeyer and Aaron Augustus Healy, the Brooklyn Museum became recognized as a serious collector of the French “avant-garde.” Indeed, the Museum opened the path for other American institutions to collect and exhibit French modernism.

As a result—thanks to donations and loans—in 1921, the Brooklyn Museum opened its landmark exhibition called “Paintings by Modern French Masters Representing the Post Impressionists and their Predecessors.” Both controversial and eye-opening, the exhibit put the Museum on the map and permanently established Paris as the place for serious American connoisseurs to seek artistic splendor. The great American photographer Alfred Stieglitz said of that 1921 Brooklyn show: “Could it be true? And in a museum? And an American one at that. Truly a revelation… I stood in the center of the room and felt a great hope.”

Beginning in 2017—as a centennial homage to that trailblazing exhibition—the Brooklyn Museum has toured nearly 60 of its greatest pieces around North America in a show called “French Moderns: Monet to Matisse, 1850-1950.” On display at the Portland Art Museum from June to mid-September of 2024, the exhibit is captivating, impressive, and revealing.

Divided into four segments—Landscape, Still Life, Portraits & Figures, and The Nude—the show certainly has its share of now well-known artists who were

either French or who made France their home: Alfred Sisley, Fernand Léger, Marc Chagall, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, et al. But what makes the show truly revelatory is the work of lesser known artists who inspired—or were inspired by—the explosion of creativity that made Paris the Ground Zero of the European art scene during the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the section devoted to broadly defined landscapes—including a remarkable oceanscape by Gustave Courbet and a backyard apple tree by Gustave Caillebotte—one of the more significant pieces is a modest 14-by-24 inch scene from the early 1890s called The Beach at Trouville by Eugène Boudin (1824-1898). Boudin was absolutely committed to painting en plein air, in this case to capture, in deeply saturated patches of often bold color, the play of light on the clouds, water, and expansive sand flats. This method had a permanent influence on his young friend and occasional student Claude Monet who would go on to make plein-air his go-to process for the rest of his life. Works like this one established Boudin as a significant forerunner of the Impressionists.

The term “Still Life” is also treated loosely and imaginatively in the show. The Carpet Merchant of Cairo by Jean-Léon Gérôme and An Embarrassment of Choices by Jehan-Georges Vibert at first glance appear to be portraits of a merchant and a Roman Catholic cardinal respectively, until you realize the focus is really on the carpets and on an enormous vase of flowers. A similar “misdirection” occurs in József Rippl-Rónai’s Woman with Three Girls. The 24-by-36 inch oil on board from around 1909 shows the influence of his friendship with the group of Parisian artists called The Nabi Circle (see my article on the Nabi in Gallery&Studio, Winter 2022, Vol. 3, No. 2). Rippl-Rónai (b.1861) spent 1887 to 1900 in Paris before returning to his native Hungary where he lived until his death in 1927. The woman in the center of his painting looks at three girls squeezed into the far left of the canvas, but what the viewer begins to focus on are all the floral elements of work: the flowers that trim the table cloth, the two hefty bouquets of flowers on that table, and—most prominently—the flower-print wallpaper that dominates the entire background. The four women become peripheral to the real “stars” of the picture. For the curators to call this a “still life” is both wink-filled and thought-provoking.

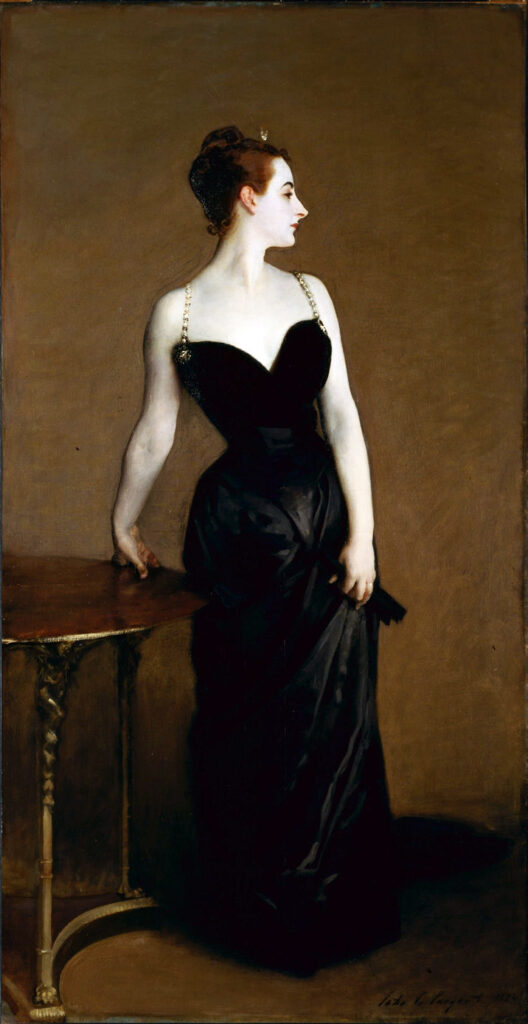

Completed in 1912, one of the most dramatic works in the show is the 91-by-47 inch life-sized Portrait of a Lady by Giovanni Boldini, an Italian-born genre and portrait painter who lived and worked in Paris for most of his career. The choreographic position of the body; the open look on the face; the earth tones of the background and chaise; and the sensuous, slipped sleeve of the black dress all have a familiar quality to them. And they should. Boldini (1842-1931) was the exact contemporary of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), and both men were great friends. Both also made fortunes painting enormous portraits of the rich and famous. When Sargent created his infamous portrait of Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau) in 1883, Paris was shocked, and the painter sold his studio to Boldini and exiled himself to London. By the time Boldini painted his similar, stunning portrait of Florence Blumenthal nearly 30 years later, Paris had embraced—and celebrated—such suggestively opulent works.

The final section of the exhibition celebrates “The Nude”—from Rodin to Degas. One of the most powerful works is Model Washing her Hair from 1929, a nearly square 21-by-23 inch tempera on linen created by Aleksandr Yakovlev (1887-1938). Yakovlev was born in Saint Petersburg but became a French citizen shortly after the Russian Revolution. In Paris, he became known as a remarkable draftsman and—thanks to the influence of Georges Rouault—a leading realist/expressionist. The work in this show doesn’t display any traditional grace. No, the woman’s squatting, muscular form fills the canvas, and the monochromatic palette creates an impression that is both dark and claustrophobic. The bather performs her ordinary task, oblivious to our gaze, and becomes a character out of Zola or Balzac, a cog in the drudgery of the world.

“French Moderns” certainly gives us the Top Ten names of French art from the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries, but it is the work of the lesser-known artists that often stands out. We discover the context for the household names and realize the full-depth and richness of the period and the location. The show also reminds us—once again—of the importance of the Brooklyn Museum as one of America’s great cultural treasures. G&S

Leave a Comment