Arnolkis Turro works on canvases that appeal to visual sensitivity without being formalistic, hedonistic, or a painting about painting.

The artist was born in Guantánamo, an eastern province of Cuba. He graduated from the National School of Art in Havana (ENA) in 1996, when the once prestigious institution closed permanently. Five years later, the painter left the Caribbean island. After residing in Germany, Spain, and the United States, he settled in Nicaragua, where he recently expanded his studies. Turro withdrew to a rural environment, distant from the hegemonic cultural centers. His experience as an emigrant has contributed to enriching his painting.

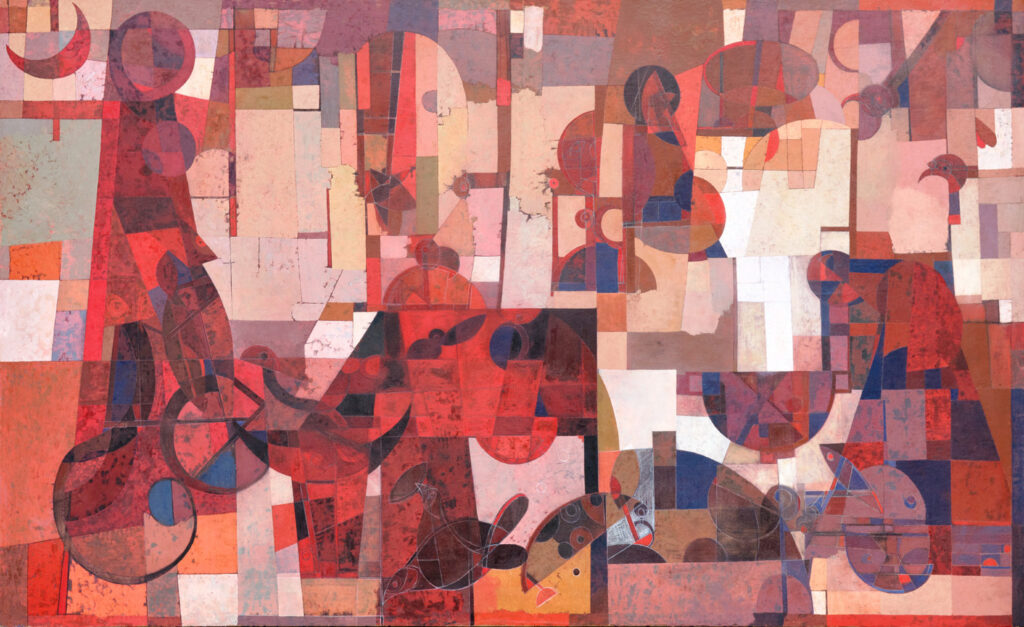

For the triptych Promesantes (2023), Turro was inspired by Nicaraguan patron saint celebrations, in which the promesantes—religious pilgrims or promisors who offer tributes to the patron saints—occupy a central place. The painting seems to trace a transition from the figurative to the abstract. In the panel on the left, the faces of the promisors have the appearance of masks or phantasmagoria. However, in the central canvas, and even more so in the one on the right, the artist seems to change his point of view, as if in the procession—now perhaps captured from above, from a bird’s-eye view—the individualities were diluted in the collective enthusiasm, in the movements of the crowd, in the bustle that takes on an increasingly abstract aspect. Red, which is one of the most striking features of these patron saint’s festivities—appears in many of the celebration’s typical costumes, body decorations, and floats—becomes a metaphor for the popular celebration. It unfolds as an immense field of color, within which it is possible to enjoy subtle chromatic harmonies, expressive gestures, sequences of lines, and transparencies.

In another of his triptychs, Playa Lacustre (2023), we also witness a sequence where figurative references gradually lose importance without being wholly suppressed. A representation of the Virgin Mary—evoked by the triangular structure, the inclined head, and the cloak that covers her body—decreases in size, as if she were more distant, although also more chromatically closer if we look at the warm colors. In the right panel, the virgin is absent. It would seem as if she had been transformed into a plant or a flower while splashes of ink, geometric figures, and a white harmony prevailed on the canvas’s surface. Turro has stated that he wanted to “poetically communicate contemporary urban or rural narratives, rooted in the marvelous reality (real maravilloso) of Latin America.” In Playa Lacustre, the ordinary adjoins the miraculous.

With his handling of color harmonies, and more easily recognizable figurative allusions, Turro is creating works that seek to reveal spaces of intimacy in which we could speak of unconscious impulses. Spaces inspired by representations of nature, biblical episodes, evocations of saints and virgins, vernacular practices, and personal memories. This heterogeneous poetic world—which, as the Nicaraguan literary critic Álvaro Urtecho wrote, has something childlike with dreamlike roots—is expressed from a visually dazzling chromaticism through glazes, spontaneous strokes, decompositions of the figures, as well as the inclusion of graffiti and textures achieved with varnishes or pigment fillings.

Turro paints profusely, with astonishing speed. He ventures into large canvases, leaving room for improvisation. He creates chromatic chords, visual rhythms, and geometric motifs that reappear as a leitmotif throughout the canvas. The painter has expressed that the kinesthesia between music and painting constitutes one of his fundamental interests. These correspondences so attractive to artists can barely be described in words which could have the effect of homogenizing the numerous “variations on the same theme,” which immediately becomes apparent when comparing works of dozens of artists. In the case of Arnolkis Turro, the confluence between this kinesthesia and the notion of Latin American magical realism is striking.

Turro’s aesthetic concerns are similar to those that inspired artists who, in the past, worked in what today some critics have agreed to call retro-avant-garde, that is, the late and, at the same time, hybrid assimilation of the contributions of art that was novel in the first half of the 20th century, including interest in abstract expressionism. But Turro has also mentioned how his canvases were transformed after he departed from Cuba, as he became familiar with the works of artists such as Cy Twombly, Anselm Kiefer, Richard Serra, Mark Bradford, José Parlá, and Caroline Kent. These references show that the art of our time, without necessarily being parodic and without necessarily seeking to delve into simulations or pastiches, cannot escape from an intricate amalgam of intertextual and transhistorical relationships. It also participates, as Turro’s work shows, in complex international relations, encompassing tourist trips, migratory movements, visits to museums and art galleries in large urban centers, and the profound influence of the Internet on daily life. G&S

IG: @arnolkisturro

Leave a Comment