In an 1880 campaign speech, presidential candidate James A. Garfield identified the two questions of civilization as “How shall we get leisure?” and “What to do with our leisure when we have won it.”

Americans soon had the answers. By the mid-1890s, hard-fought labor reforms had shortened work days, increased incomes, and provided regular time off for many industrial workers. The growth of corporations generated a workforce of business managers, office staff, and retail professionals. As a result, more Americans could afford a day trip or a week in the country. Leisure-seekers embraced outdoor activities, from team games to excursions among mountains and lakes. Railroads and hotels promised comfortable travel and accommodations. Such invigorating or tranquil relaxation remained out of reach for subsistence-wage earners, and legalized segregation excluded many Black Americans from such opportunities until well into the 20th century. But for the enlarging white middle class, “outing” was the new colloquialism.

From his home near New York State’s Lake George, novelist Edward Eggleston observed “many thousands who give themselves up to pleasures of every healthful sort—rowing, fishing, bathing, mountain-climbing, boat-racing, canoe-racing, steamboat excursions, moonlight sailing, lawn tennis, mooning on the piazza, and other outdoor recreations, to say nothing of indoor games.”

Journalists expanded their scope beyond elite society’s pastimes such as horse-racing and yachting. The sub-titles of two magazines indicated a wide-ranging definition of leisure—OUTING: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Sport, Travel and Recreation, and RECREATION: A Monthly Magazine Devoted to Everything the Name Implies. They included articles on specific sports, accounts of foreign and domestic holidays, and nature writing. Short stories, serialized novels, and poetry celebrated the joys and challenges of the natural environment. Columnists gave advice about outdoor gear and suitable clothing, and advertisers trumpeted the latest in both.

After safety bicycles with their two wheels of equal size and pneumatic tires replaced the high-wheel “boneshakers” favored primarily by affluent young men who alarmed pedestrians, the only sport to merit the description “craze” was cycling, initially called wheeling. When women school teachers in New York City made $600 a year and men $900, bicycles ranged from $50 to over $100. But costs gradually dropped, dealers touted installment payments, and bicycles were shared among family and friends. Throughout the country, articles about local clubs, gatherings, and races were often prefaced by the words “the bicycle craze has come to…”.

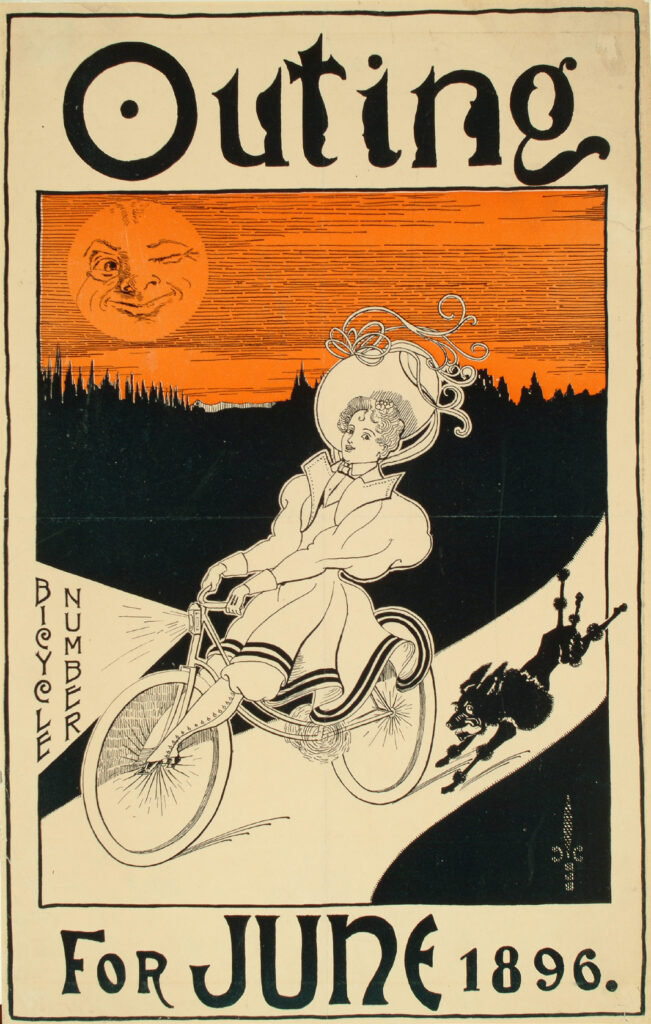

The carefree woman catching our eye from Outing’s advertising poster for June, 1896, swoops downhill under a winking moon, as her headlight illuminates the issue’s theme. Her fearless independence is accentuated as she rides alone along the edge of a dark and dense forest. Her feet have left the spinning pedals, and she confidently leans back, barely touching the handlebars: she is a study in dynamic self-assurance. Her bearing recalls the observation in “The Moderns Awheel” (Harry A. Cushing, Harper’s Weekly, April 11, 1896) that “…in all this wheeling sport there is a jolly abandon.” The cyclist is both an embodiment of the New Woman, and a free spirit ready to challenge convention. The beribboned hat, unruly curls, billowing mutton-chop sleeves, graceful skirt over bloomers, and leggings signal her up-to-date style. Her equally elegant poodle runs all-out to keep up.

“Journalists expanded their scope beyond elite society’s pastimes such as horse-racing and yachting.”

Women cyclists’ prowess and self-reliance elicited hostility at worst and ambivalence at best from both genders in various quarters. Some doctors obsessed over women’s anatomical “fragility,” especially during their “monthly weakness;” others panicked that bicycle seats would cause sexual stimulation. The Woman’s Rescue League, self-appointed enforcers of female morality, declared women cyclists “vulgar and indecent.” Numerous articles such as “Bicycling for Women: The Puzzling Question of Costume” pondered how women awheel could both protect their modesty and preserve their allure to men.

George Frederick Scotson-Clark, the artist who created this poster, was primarily a stage and costume designer and produced many theatrical advertisements. His Outing image captures both the cyclist’s literally free-wheeling attitude and the dramatic Art Nouveau swirls of her outfit, the better to induce viewers to spend 20 cents for the issue.

Women’s cycling enthusiasts outnumbered detractors. The demands of even the simplest riding attire advanced the Rational Dress Movement, which led to more functional and healthful women’s clothing for sports and everyday wear. Women formed their own professional racing circuits. Nationwide, their stars drew fans who applauded breath-taking speedsters such as the formidable Tillie “The Terrible Swede” Anderson. Kittie Knox, a Black Bostonian, defied entrenched prejudice and helped desegregate cycling. Today we remember not the critics, but Susan B. Anthony’s declaration: “I think cycling has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world…I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

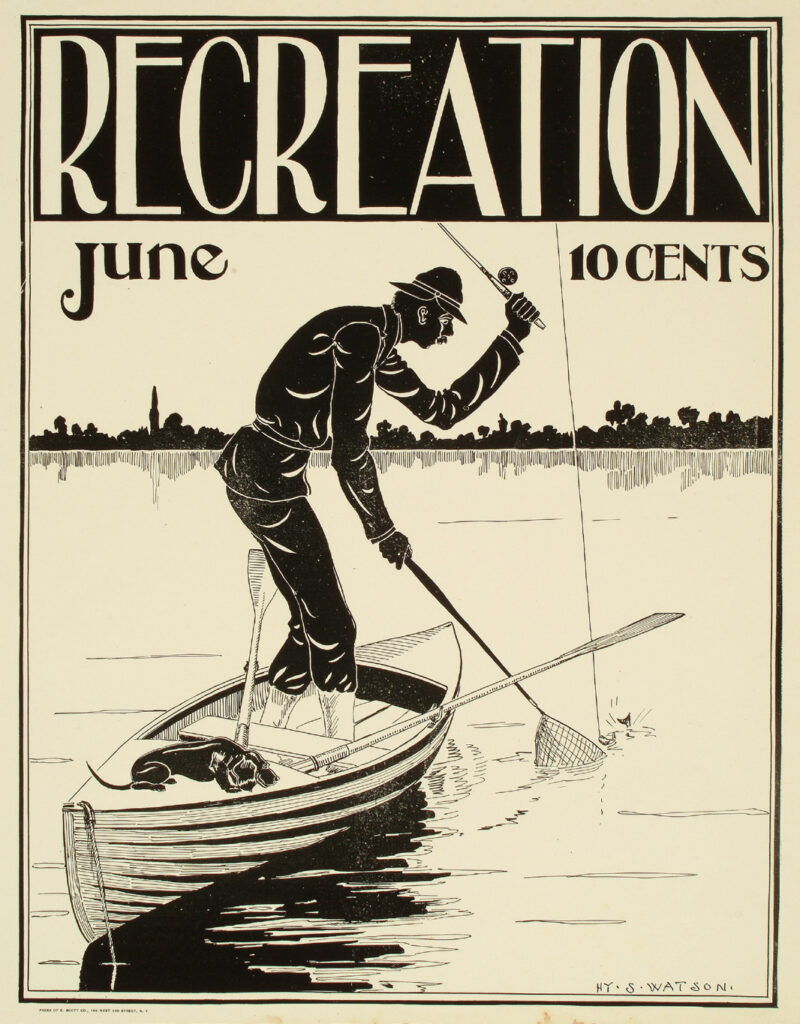

In contrast to the speeding cyclist, Henry Sumner Watson’s fisherman on Recreation’s June, 1896, poster is the epitome of controlled movement and intense concentration. In one expertly orchestrated action, he keeps his line taut as he reaches for a thrashing fish. His perfectly balanced stance causes only a few ripples in the water. The dog—apparently accustomed to such calm proficiency—gazes expectantly at the successful catch. The man’s imposing height, in black silhouette broken by spare white strokes, dominates the design. Straight lines in the fishing gear, oars, basket handle, and tree in the left background reinforce a sense of stability. The fisherman’s “joyful abandon” in the wild comes not from velocity but mastery of his skill. For 10 cents, purchasers could savor Recreation’s articles and illustrations. Henry Sumner Watson specialized in hunting and fishing scenes, which later led to his editorship at Field and Stream magazine.

Nor were men necessarily alone in the enjoyment of the sport. In “A New Hand at the Rod” (Outing, May, 1890), “C.R.C.” asserted that “Woman’s hour has struck. I will go fishing.” Maine angler and sports promoter Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby helped popularize more practical fishing and hunting dress for women.

The presence of Black fishermen, notably in the South, infuriated enough people that Jim Crow laws around the sport were tightened. At the turn of the 20th century, similar segregation led higher- and middle-income Black Americans to establish their own vacation enclaves, including Highland Beach, Maryland, founded in 1893 by Frederick Douglass’ son Charles. By 1912, Idlewild, Michigan, was an active Black resort community.

In the 1890s, posters, trade cards, billboards, handbills, postcards, and newspaper and magazine advertisements competed for American eyes. Scotson-Clark and Sumner Watson created evocative images that validated art critic M. H. Spielman’s comment in Scribner’s Magazine (July, 1895) that a “poster of real beauty proclaims itself gently, but irresistibly…and…is an artistic triumph of which any artist might be proud.” G&S

Leave a Comment