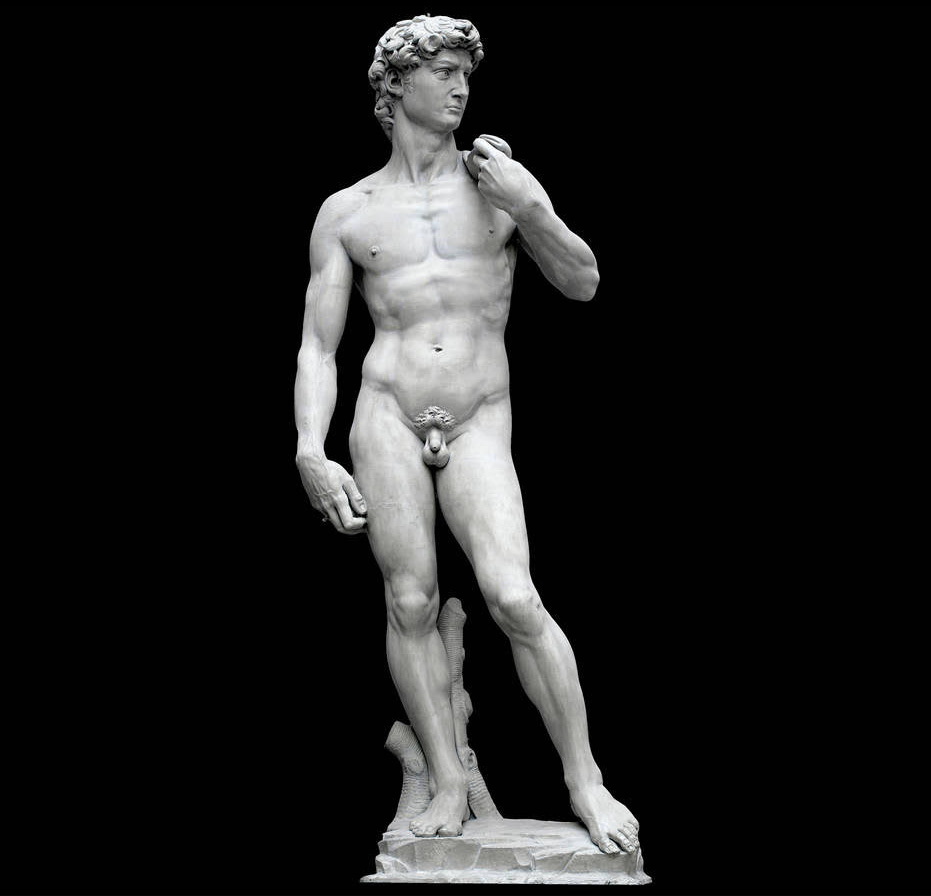

In 1989, upon entering the Pushkin Museum in Moscow for the first time, I was totally shocked to discover that Michelangelo’s David, which I had seen in Florence, had been moved to Moscow. At first I thought it was perhaps on loan, only to discover fairly quickly that I was looking at a plaster cast. Quelle surprise! A little further on I was confronted by Michelangelo’s Tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici, with the statues of Night and Day, that also had formerly been in Florence. But of course, it was also a copy. In fact, the museum was full of copies, in addition to its world-class collection of originals, including works by Rembrandt, Canalleto, Munch, Monet, Van Gogh, Matisse, Chagall, and many more. (Note that the David on the Piazza Della Signoria in Florence is also a copy; the original is kept in the nearby Galleria dell’Accademia. So most visitors to Florence are also seeing a copy.)

As most Russians cannot travel abroad, the copies give them the opportunity to see what to most people look very much like the originals. A significant portion of the collections of both the Pushkin Museum and The Hermitage was acquired in the 1920s by the Soviets when they nationalized the private collections of the most important Russian collectors–the Iusupovs, the Stroganovs, the Shchukin brothers, Ivan Morozov, et al. Some of the nationalized works were sold to Western collectors, including Andrew Mellon, who later donated his collection, under duress due to tax issues, to what became the National Gallery in Washington, DC. That’s how the National Gallery acquired its Da Vinci.

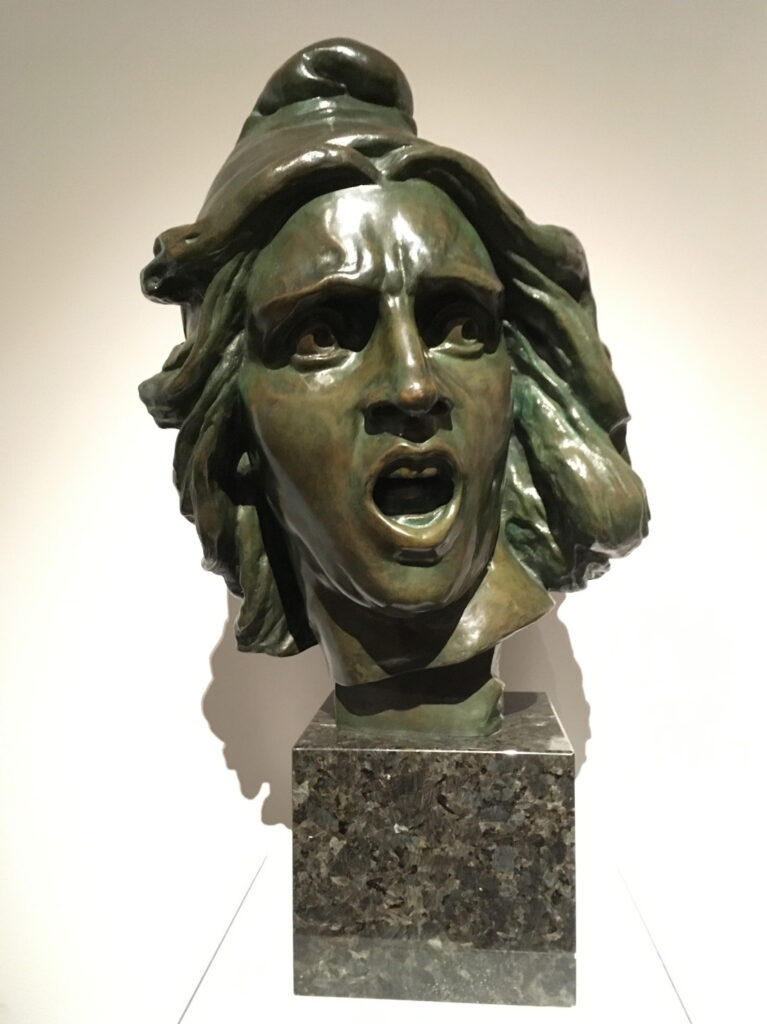

The first time I saw a collection of copies was in 1979 at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh (and most people in Pittsburgh also can’t travel around the world). Next, an even greater surprise was the Victoria and Albert’s copies in London! Another David by Michelangelo! At first I was horrified, but I realized that it was in the service of providing an educational experience to millions of people who were never going to see the originals. Twenty years ago, for instance, I saw another such collection, in the tiny Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga, and I learned that in the 18th and 19th centuries, collections of plaster casts could be found in most European cities, but I’m not aware of others. If they still exist, I don’t think they are on view, like the bulk of the holdings of most major museums.

The Carnegie’s Hall of Sculpture, according to their website, was originally designed to house Andrew Carnegie’s personal collection of 69 casts of Egyptian, Near Eastern, Greek and Roman sculptures. The design of the hall was inspired by the Parthenon in Athens. The Caryatid porch of the Erechtheum, near the Parthenon, is one of the most copied, painted and photographed monuments in the world.”But what we see there nowadays are copies. And having seen both the originals in place and, more recently, the copies, I don’t think there was one iota of a different experience.

The Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection of copies, like those of the Pushkin and the Carnegie Museums, exists to make foreign works of art readily available to locals, even though Brits seem to do a lot of traveling. But coming upon them while visiting the museum does leave one puzzled. However, in the Musée National des Monuments Français, the French have created a very special collection of reproductions of French architectural monuments, including famous statues, parts of churches and portals of major cathedrals–Chartres, Reims, Amiens, Rouen and Notre Dame. The idea is to maintain protected copies of these magnificent works in the face of the constant deterioration of the originals due to natural causes, and as in the case of Notre Dame, fires. The copies can be used for planning restorations. It’s not a museum often visited by tourists, or even by Parisians, but the concept is spectacular and demonstrates the French commitment to French culture and their national patrimony.

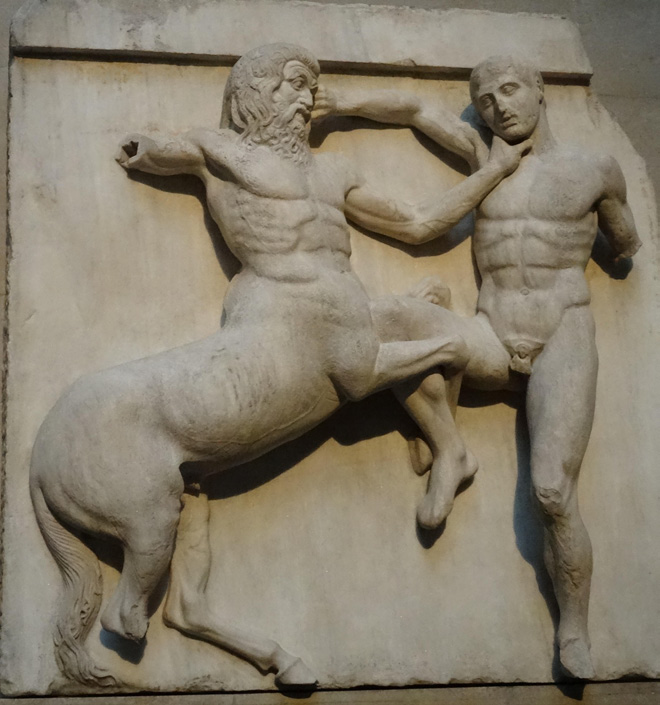

Roman collectors from as early as the fourth century B.C. amassed great plaster-cast collections of recognized masterworks, with the idea that a copy of a great work was superior to a mediocre original. In the same period, Greek and Roman artists began creating marble and bronze copies of famous Greek statues to meet the great commercial demand for such works as the Roman middle class became more affluent. Sadly, original Greek statues made from tin, and later Bronze copies of tin and marble originals, were mostly melted down for the production of armaments and as building materials. It’s the reason the Met, the Louvre, the British Museum, the Hermitage, and other major museums, more often have Roman copies of Greek works than original Greek statues, although most museum visitors are hardly aware of this unless they read the labels. And of course we are thrilled to see these 2000-year-old copies, many of which are magnificent.

Underlying all of this is a totally separate question–patrimony. How is it that there are so many Greek and Roman statues in great museums outside Greece and Italy? The Met and other museums have lately been returning dribs and drabs, while Greece has long been demanding the return by the British Museum of the marble statues that formerly adorned the Parthenon, and are now known as The Elgin Marbles. Meanwhile, at The Acropolis Museum there are plaster copies of some of the Elgin Marbles!

Another case in point is the wonderful collection in the Pushkin Museum dubbed Priam’s Treasure, consisting of Greek gold jewelry smuggled in the 19th century out of Hisarlik, Turkey, the presumed site of ancient Troy, by Heinrich Schliemann, a German amateur archaeologist. Schliemann thought he was rummaging through the ruins of Helen’s Troy. He was in roughly the right place, but he was in the wrong century, and she left no inventory of her jewelry, so it’s not clear whose gold he found. He is especially famous for taking a photo of his wife wearing some of the jewelry, all of which he brought to Berlin. With considerable chutzpah, Germany considered it German. However, the Russians “relocated” the collection to Russia toward the end of World War II, to compensate, they said, for the incredible amount of destruction Nazi Germany had wrought on Russia, and for the many cultural treasures the Nazis had destroyed.

The Russians kept it a secret for 50 years, but it’s now one of the most popular attractions in the museum, while the Germans have only a few bits and pieces, and some old photographs (in the Neues Museum in Berlin). Thus, treasures from an ancient Greek city, dug up in present-day Turkey and brought to Germany, are now mostly in Russia. (Around the same time that the Pushkin first displayed Priam’s Gold, The Hermitage presented a huge collection of Western art that was also acquired in Germany as spoils, dubbing it “Hidden Treasures.” Mikhail Piotrovsky, Director of The Hermitage, in announcing the show, claimed that he had only learned quite recently that the horde was in their basement. He said that the prior director had never mentioned it to him because he had been sworn to secrecy by his Soviet superiors. The prior director was his father!)

So perhaps all originals should be returned to their original owners after plaster copies are made to satisfy and educate local audiences in the countries that raided other countries? G&S

Norman Ross has visited all of the museums mentioned in the article, generally multiple times.

Leave a Comment