Almost a century passed between Lewis and Clark’s 1804-06 expedition and the government’s 1890 declaration that the frontier was closed. During those years, most Easterners never traveled to the nation’s expanding western territories and states, although they may have seen romantic paintings and documentary photographs of landscapes, wildlife, settlers, and indigenous North Americans. About mid-century, covers of dime novels (“Books for the Million!”—used as a slogan by the Beadle Dime Novel Series ) blazed with gun-wielding men, fearful women, and rampaging Apache or Sioux warriors. Currier and Ives’s images (who described themselves as “Publishers of Cheap and Popular Prints”) highlighted men fighting wildfires or hunting buffalo, created by artists who had witnessed neither. Artist-correspondent Frederic Remington’s magazine illustrations included first-hand scenes of cattle-ranching, US cavalrymen, and Native Americans. The rugged, self-reliant “cowboy” became a recurrent motif. Women’s roles in such mostly male activities were usually secondary at best.

Reality belied literary and visual stereotypes. Women were among the half-million plus people who walked with wagon trains, endured lengthy stagecoach journeys, or—after 1869—rode the trans-continental railroad. White and Black, a few alone but generally with family, many were burdened with pregnancy, childcare, and domestic chores during the arduous migration. Some idealistically sought freedom from social and legal restrictions, including slavery and its aftermath.

Once settled, women commonly faced isolation, poverty, illness, and lawlessness. They encountered violence with Native Americans, who were systematically dispossessed of land and culture by government edicts, settlers’ aggression, and military force. Still, many women built new lives in the West.

Some of them related their personal observations. Mary Hallock Foote produced the 1888-89 series “Pictures of the Far West” for The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. Before Hallock Foote married mining engineer Arthur De Wint Foote in 1876, she was already a successful illustrator. She continued her career as she accompanied him to jobs in California, South Dakota, Colorado, and Idaho. Her income and status spared her many personal hardships, and she was a keen observer and recorder of women’s lives.

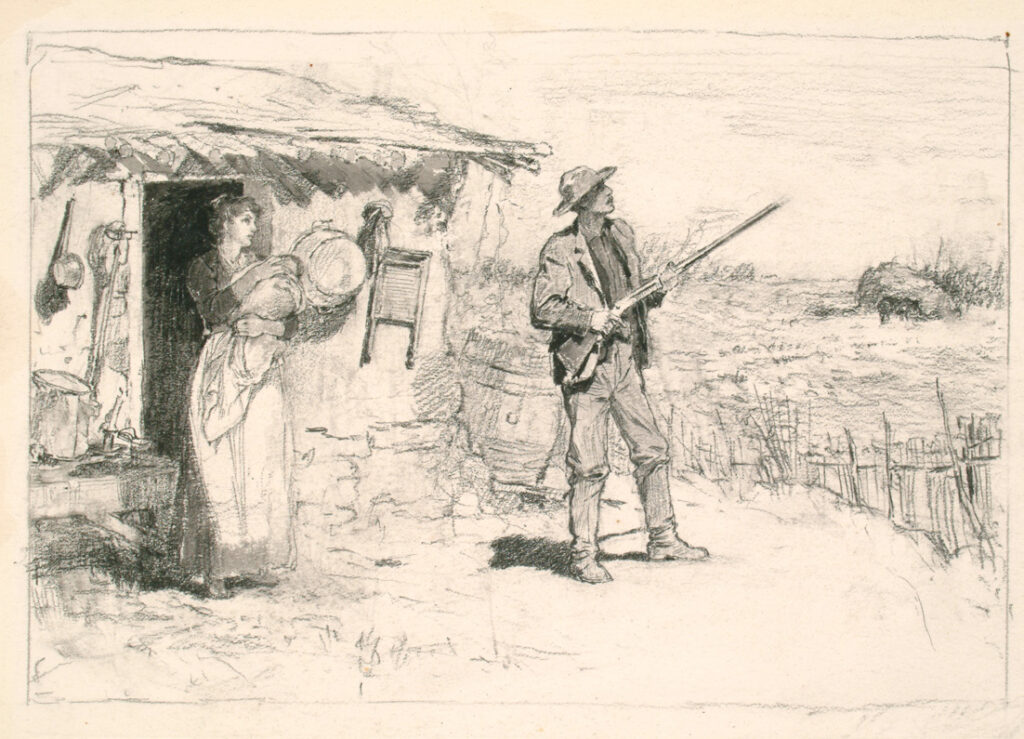

Study for The Coming of Winter, 1888. Illustration for Pictures of the Far West, by Mary Hallock Foote, in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, December 1888. Graphite and ink on paper, sheet: 5 5/16 × 7 3/4 in. (13.5 × 19.7 cm). Delaware Art Museum, Acquisition Fund, 1991

In her study for The Coming of Winter, a couple stands outside their mud-cabin on near-barren ground. The wife’s cooking and laundry tools are nearby. As her husband looks up, ready for “a chance shot…that may furnish a meal,” she protects her infant’s ears from the gun’s report. In Hallock Foote’s portrayal of this imaginary couple, the husband is one of the “restless men who have the inevitable vague westward impulse.” His wife reluctantly joins him, and “grows listless” as the wagon train drags on. Finally settled in their rudimentary home, he yearns again for “the freedom of the road,” whereas the woman—now a mother—is ambivalent, and the couple’s future uncertain.

By the early 20th century, Wild West shows were giving Americans a new vision of the “old West.” These extravaganzas, which included theatrical presentations of Western life (“Enactments So Colossal You Can’t Imagine!”), sensationalized and usually fictionalized what Theodore Roosevelt called “the rapidly vanishing West.” “Buffalo Bill” Cody, “Wild Bill” Hickok, and Geronimo were nationally-known stars. Annie Oakley and “Calamity Jane” Canary were among the women in the male-dominated arena.

Increasingly, women saw themselves reflected in illustrated fiction. Owen Wister’s 1902 novel The Virginian enshrined the image of the strong-willed cowboy tempered by a women’s love; a stage play based on the book toured for 10 years.

Hollywood capitalized on the trend. In 1923, the silent movie The Covered Wagon centered on a determined man who overcomes dangers and villains as he leads a caravan West, partly driven by his love for a woman. He not only wins her over, but also strikes gold, for a happy and prosperous ending. The Los Angeles Examiner’s critic was impressed that “Ideals and adventures go hand in hand, and romance winds throughout the film.”

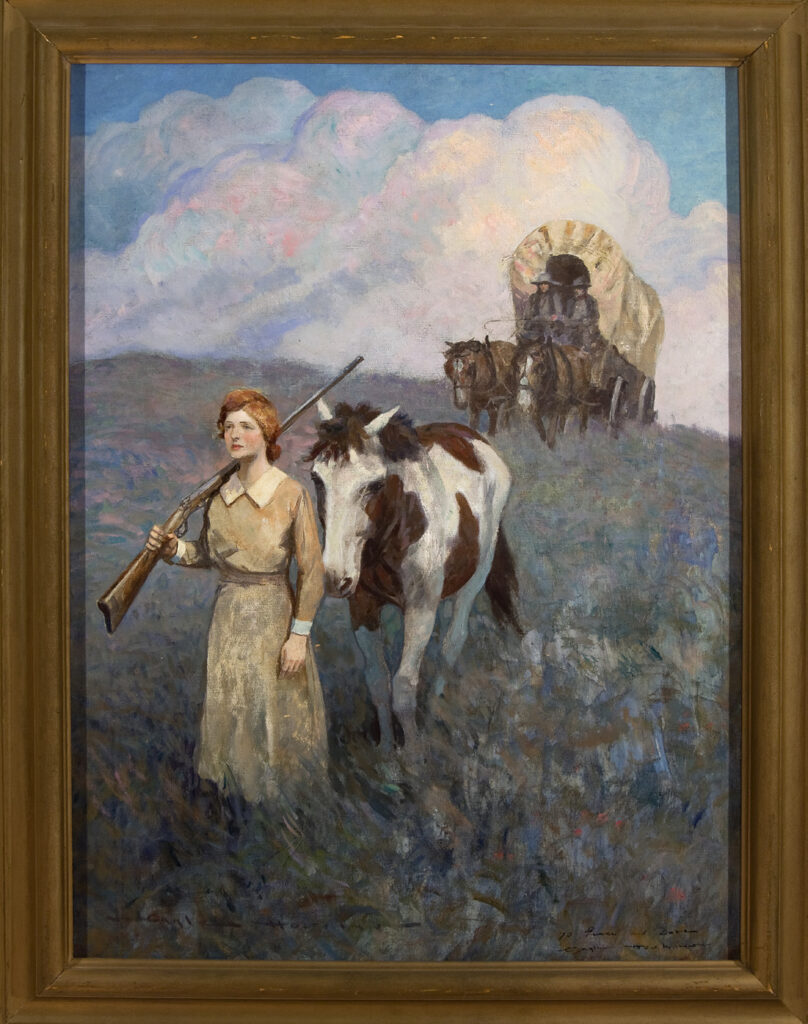

Mort rode forth boldly toward the sod house, 1926. Illustration for “Oklahoma,” by Courtney Ryley Cooper, in The Country Gentleman, May 1926. Oil on canvas, 26 × 36 1/2 in. (66 × 92.7 cm).

Delaware Art Museum Gift of Mrs. Harald de Rapp, 1971

The hero of Courtney Ryley Cooper’s 1926 serialized novel Oklahoma exemplifies the new combination of cowboy strength with emotional sensitivity. Frank Schoonover’s illustration shows us a woman named Mary working outside her primitive house. She spies Mort, the enterprising cowboy-pioneer who has proposed to her. However, she feels obligated to care for her orphan nephew and his abusive father. Mort respects Mary’s dedication to feminine duties but gently persists with his proposal. Events free her from the self-sacrificial moral quandary, Mort nexpectedly gains a fortune, and their future together is ensured.

Ryley Cooper, known primarily as a short story writer and crime journalist, was also an Annie Oakley biographer, and a publicist for a Wild West show. Frank Schoonover, whose studio was in Wilmington, Delaware, spent time in Montana and Western Canada, where he garnered sketches and photographs that enlivened his illustrations.

Teen-aged Janet—fearless daughter of a Kansas settler family—dominates Margaret Lynn’s serialized 1926 story The Gathering Storm. In Gayle Hoskins’s illustration, she comes upon the men who stole her pony, Pronto. Well-armed, she matter-of-factly seizes Pronto and begins to walk him home as the rustlers mockingly accuse her of thievery. Unintimidated, Janet offers them food and shelter if they follow her. The men, impressed by her bravery, “cease(d) to be amused” and accept her hospitality. Janet tells her parents that she plans to return to the West after college for a life of “courage and devotion and firmness.” Men do not figure in her plans.

During Hoskins’s youth in Colorado, he gained first-hand knowledge of Western scenes before he established his studio in Wilmington, Delaware. A native of Missouri, Margaret Lynn migrated with her parents to the remotest part of the state during her childhood. She became a college English professor and was among the first women to write Western novels. Some critics consider Lynn’s character Janet a fictional portrait of herself.

Late 19th and early 20th century representations of Western women in popular culture often blended harsh realities and nostalgic myths. In the 1970s, women historians began systematic studies of women’s presence in Western history. Primary sources such as diaries have also revealed direct evidence encompassing formerly-ignored women outside the Euro-American tradition. Thanks to recent research, authors and artists now have a much wider and richer view of women’s “courage and devotion and firmness.” G&S

Mary F. Holahan © 2024

Delaware Art Museum delart.org

Leave a Comment