Paul Klee said, “Art does not reflect what is seen, rather it makes the hidden visible.” The invisible is the conscience of society’s soul. It informs and enriches us with its presence in our lives.

The past one hundred years have given us brutalities still deeply affecting, and sans the rosy lens, society is portrayed more honestly now, unvarnished, without insipid veneers.

We chase what we term “human advancement” based on our history of repeated cruelties, and today find ourselves living in a time of rapid technological change. Our Fourth Industrial Revolution, arising from the previous earth-shaking Third, stresses both body and soul.

Artists, historically, are not born to great monetary wealth and power, and live as attentive observers to the societal milieu of which they are “part but not parcel.” They make art as healthy coping mechanisms, a balm for anxieties from repeated psychic assaults. Their special task is to identify and transmogrify the costs of challenging human actions. Art brings healing and composure to both flesh and spirit’s unsolicited wounds, particularly helping us when authoritarianism rears its insidious head.

A recent retrospective exhibit of the late African-American painter Michelangelo Lovelace celebrates vitality while responding to social diffidence with acerbic and witty commentary on race. Lovelace’s epic painting, You Have the Right to Remain Silent, brings forth life on urban streets, his almost naïve depictions of race and ethnicity tempered by the work’s title referring to Miranda Rights. The artist’s portrayals are ebullient, while, in tandem, undertows of social tensions are strongly felt.

Theater pieces like Hair and the revue, Inner City: A Street Cantata based on fairy tales for children and adults can also be seen as examples of forerunners to Lovelace’s paintings, remaining timely because of America’s persistent societal stressors.

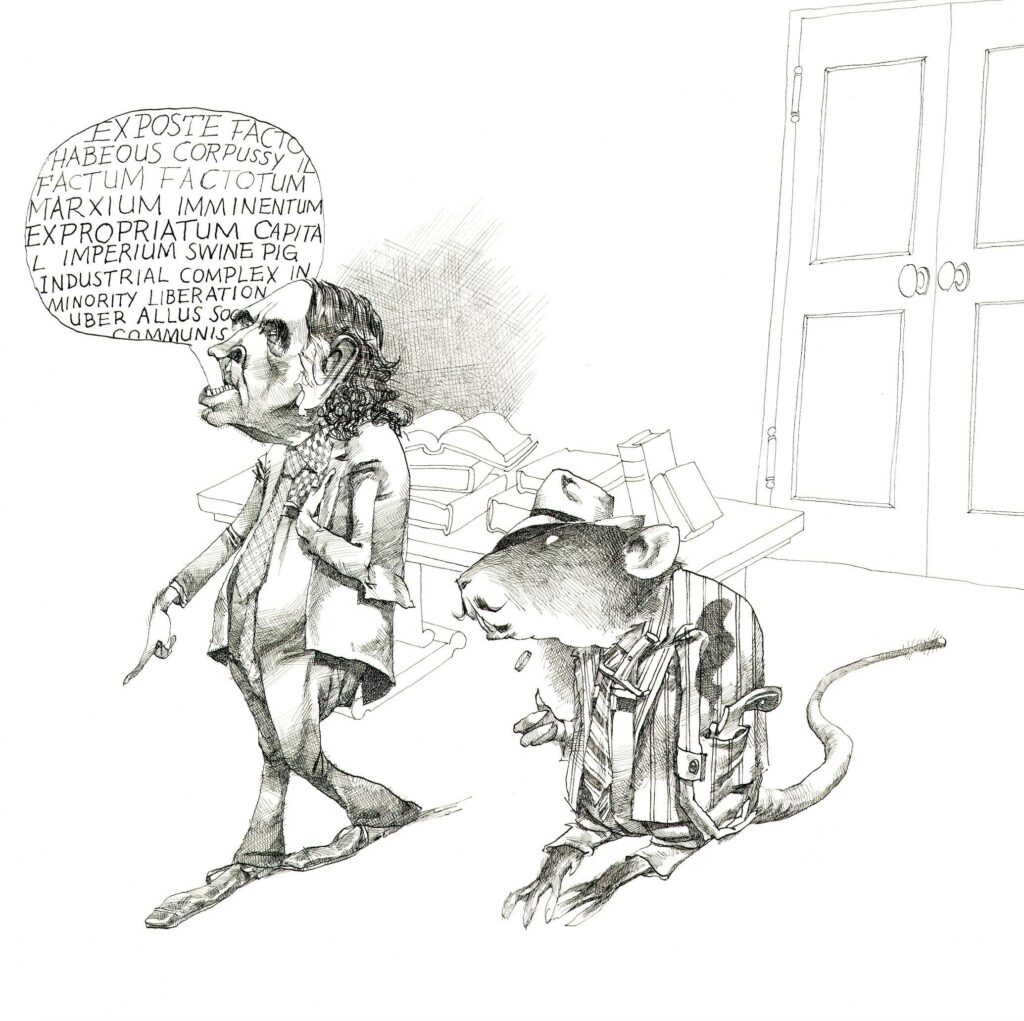

In the late great New York artist and political satirist’s “choice” words and drawings in his book, Mickey Rat, Ed Henrion sends up US life and times through the politically incorrect lens of urban rodent, immigrant, Mickey Rat, who envisions our country’s streets paved in cheese. Unfortunately for him, they are not and instead, the rat provides scathing fuel to the fires of the misbegotten adventures of Street Cantata and Ruckus Manhattan denizens, via graphic renderings that also bear kinship to satirist David Levine’s caricatures.

Red Grooms, with journalistic flair, ironically exposes Gotham’s contemporary life in his mixed media extravaganza Ruckus Manhattan, skewering town and citizens alike with a brilliantly risible hot poker. His sly spirit infects his panoply of scenes and characters, perhaps implicitly affecting Lovelace’s adroit depictions.

It might also be said that art as social commentary and political satire are greatly indebted to artists such as George Grosz and Paul Klee who after World War One created scathing commentaries as reactions to the conflict’s trauma.

Grosz’s painting, Republican Automatons depicts Weimar supporters as mindless, faceless robots inhabiting an impersonal cityscape where despair dominates. Klee’s The Great Emperor Armed for Battle paints a sinister and comical picture of militarism, both works devoid of any modicum of optimism in their bleak renderings.

In the 1960s, James Rosenquist’s painting F-111 satirized the complicity between the Vietnam War, consumerism and the media. The large, cynical mural, disturbing in breadth and subject-matter was unlike any other work seen previously. Through the plastic realization of Pop Art, it is prescient, prophesying today’s worship of industrialized technology.

Great films such as Bertolucci’s historical 1900 and Chaplin’s sublime comedy The Great Dictator also masterfully depict prejudice and totalitarianism. Chaplin’s concluding monologue stirs us and awakens our consciences to confront evil.

Art that is unsettling can cause us to act, making a difference in society. Ultimately, after we integrate any critical stings of sarcasm, we hope the outcomes will be good. Our need to thrive provides us with more than ample reason to remain on life’s difficult highway, despite the many serious and tragic roadblocks encountered along the way. Art’s divine help eases our ardent supplications. G&S

Leave a Comment