Walking westward along 14th Street, two statuesque women in impossible heels came towards me, impeccably dressed in black, followed by a man in a tuxedo with just enough of a 5 o’clock shadow to look dangerous. I glanced into a shop window, where a very smart looking security guard looked towards me with a ubiquitous secret service-style ear piece. Chic restaurants spilled onto the sidewalks and high-end boutiques winked their wares from their pristine windows. I wondered if I had stumbled onto a movie set, falling Alice-like into a parody of New York a la ‘Sex in the City’.

Fifth Floor West End

It made me wonder if the Whitney, with its new ‘responsive W’ logo and its new Renzo Piano designed home in the ‘glamorous Meat Packing District’, was going to be so trendy and ‘A’ list, that it would be uncomfortable for mere plebeians like me. I admit to a personal sentimentality to the previous building, built by Marcel Breuer on Madison Avenue. That womb-like building with little natural light was where I first started my serious study of contemporary art, where I got to know the likes of Hopper, Calder, O’Keeffe, LeWitt, and Oldenburg; trying to understand the development and the drivers of American artists.

So it was with trepidation and some reluctance that I was visiting the museum’s new home.

I need not have worried. I turned the corner onto Washington Street and smelt it. The waft of raw meat. The heart of the old neighborhood was still beating. I saw Hector’s Café and Diner. The old place was still there, only accepting cash, serving blue plate specials and apple pie. I walked under the High Line and up to the museum with a lighter step. The building is all glass, steel and concrete, anchored with Danny Meyer’s latest swanky restaurant … but flanked by a fleet of hot dog carts and with the NYC sanitation department in the background! This was still the stewpot of New York.

Robert Henri, 1865-1929 “Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, (1916)” Oil on canvas, Overall: 49 15/16 x 72in. (126.8 x 182.9 cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Gift of Flora Whitney Miller 86.70.3

HISTORY

The Whitney owes its inception to its namesake the sculptor, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875-1942), great granddaughter of one of the richest men in American history, railroad and shipping magnate, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the wife of Harry Payne Whitney a wealthy lawyer and philanthropist. In 1989 Gertrude visited the studio of John La Farge. In purchasing his work she initiated a desire to start acquiring works by American artists at a time when it was at best unfashionable and at worst radical to buy them. It was not her aim to create a collection but merely to support the artists in whom she believed, giving them financial support and artistic recognition, allowing them to follow their artistic instincts.

In 1907 Gertrude bought a studio in Greenwich Village, where she was able to work seriously as a sculptor. It became a meeting place for artists and her reputation as an artist and a patron of the arts grew. She hosted several private exhibitions but realized that a purpose-built space was necessary to exhibit the artists that she was supporting. In 1914, she established the Whitney Studio to promote American artists, presenting more than 30 exhibitions in the following 14 years, helped by Juliana Force. Additionally she created the Studio Club and Shop to provide a social meeting place and a retail outlet for their art, which was eventually replaced by the Whitney Studio Galleries. By 1929 however, Gertrude and Juliana felt strongly that a collection, housed in a museum, was necessary to further promote American artists and their art. Gertrude offered her collection of some 400 pieces to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. However in a quirk of fate, they condescendingly refused her offer. It didn’t take Gertrude and Juliana long to make the decision to start their own museum for artists.

The doors to the Whitney Museum of American Art opened in November 1931. During the following 83 years, the museum moved twice, changed its position on what constituted “American” as well as what gifts and donations to accept and from whom. The tenets for acquisitions changed frequently and the collection eventually grew to 22,000 pieces. It was time for a new home.

NEW HOME

So here is the latest home of the Whitney. Renzo Piano, an Italian architect created a space for American art that he defined. “Art is freedom, but American art is especially free, bit wild, slightly impolite but free”. He built a museum that he feels is worthy of this art. I use the term ‘space’ because the building provides it. The building has 50,000 square feet of gallery space and 13,000 square feet of outdoor sculpture terraces that cascade down the side of the building from the 8th floor and brings you within touching distance of the fashionable, elevated, urban park, the High Line.

There are vantage points that allow you to see across the Hudson to the Wild West. To the East the wild city of New York is laid out with the Con-Ed and Empire State buildings vying for attention with the iconic watertowers and the streets below.

The inaugural exhibition, America Is Hard To Find, is a retrospective of American art from 1901 to the present day, taken entirely from the permanent collection, bar one piece on loan. It is divided into four eras and 23 chapters with an additional exhibition of some of the members of the original Studio Club on the free-entry first floor gallery. The entire exhibition has some 600 pieces of artwork by 400 artists that the curators have chosen to show the depth and breadth of 115 year of American art. The broadly chronological order allows the novice to understand the historical development of styles and concepts. The chapters are an interesting way of creating themes or miniexhibitions to interest some of the more experienced or jaded art viewers. Some of the ideas are stronger than others and one or two were a stretch, but it was a Herculean task that they undertook well. With so many iconic, strong and rarely seen pieces it was hard to pick the highlights.

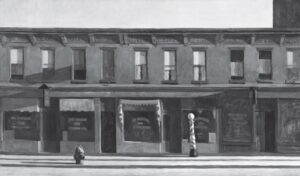

Edward Hopper, 1882 1967, ”Early Sunday Morning, (1930)” Oil on canvas, 35 3/16 x 60in. (89.4 x 152.4 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.426 © Whitney Museum of American Art

One of my favorites is Lee Krasner’s “The Seasons” painted the year after her husband, Jackson Pollock, died in a car accident. I have always thought that Krasner was the stronger painter of the couple and for the Whitney to give her, her own wall from where she regally surveys her colleagues’ work–including her husband’s smaller painting–seems as a just display of her standing in history. The label quotes Krasner “…the question came up whether one would continue painting at all and I guess this was my answer.” She same out with paint brushes blazing. I was also mesmerized by Peter Saul’s “Saigon” painted in 1967. The practically fluorescent colors and exaggerated imagery at first glance seem comical, until a further study shows his vehement condemnation of the Vietnam War. I found it hard to look at but it kept me hostage for a long time.

There are several chapters that were really powerful and could easily be standalone exhibitions. Machine Ornament, on the 8th floor, brings together art depicting industrialization and mechanization after World War I. Elsie Drigg’s “Pittsburgh,” is an oil painting of the steel mills that she admitted “shouldn’t be beautiful. But it is.” Joseph Stella’s “Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an old Theme” painted in 1939 is an oil on canvas but could easily, at over 70 inches tall, appear as a stained glass window in an old stone church. It is dynamic and whoever wrote the label for it was obviously as impressed as I was, using the term “awesome” in his description of the bridge. It’s not a term you expect from a cultural institution such as the Whitney, but I know how they feel!

In Breaking the Prairie, on the 7th floor, Edward Hopper’s “Railroad Sunset” is very evocative. It’s one of those paintings that I see very differently depending on my mood. I can see it as being glorious, sad, provocative, menacing and peaceful and much more depending on the day. Bill Traylor’s “Walking Man,” a blue silhouette of an elegant man with a walking stick and a grey tall hat, is one of those works which were a bit of a stretch to be included into this chapter, as he was a native of Alabama which, when I last looked, wasn’t a prairie and the man could be walking anywhere let alone a prairie. None the less, Traylor is an excellent example of both folk art and self-taught genres.

Rose Castle which features artists influenced by Surrealism has two iconic Edward Hoppers as well as George Tooker’s “The Subway”; three different mediums by Man Ray and a very powerful, beautiful and somehow compassionate painting of a dead black crow by Andrew Wyeth, “Winter Fields.” These all lived up to the unsettling, psychologically twisted and mesmerizing reputation of this genre.

White Target is the minimalist chapter, starring Frank Stella, Agnes Martin, Ellsworth Kelly, Jo Baer, John McLaughlin and Ad Reinhardt’s “Abstract Painting,” the totally black canvas which after careful scrutiny gives up its secret of nine squares, and was admirably explained to a skeptical museum visitor by docent Katherine Cerullo. Carmen Herrera‘s “Blanco y Verde” is a new acquisition and a nice addition. A surprise omission was Clyfford Still. The museum has only three of his pieces, but the fore-father of abstract expressionism could have merited a space.

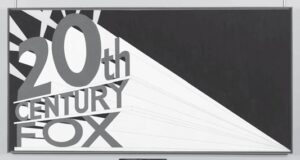

Edward Ruscha (b. 1937). Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights, 1962. Oil, house paint, ink, and graphite pencil on canvas, Overall: 66 15/16 × 133 1/8in. (170 × 338.1 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Mrs. Percy Uris Purchase Fund 85.41 © Ed Ruscha

On the 6th floor, Large Trademark has the iconic Jasper John’s “Three Flags,” Andy Warhol’s “Green Coca-Cola Bottles” and Claes Oldenberg’s “Giant Fagends.” The one stand-out however is Malcolm Bailey’s untitled work. At first glance it looks like a blue-print schematic, with a logo in the middle. It is actually a representation of a slave ship, outlined in bodies with a drawing of a cotton plant the beautiful image in the center. It made me stop and think of the slave trade.

The 5th floor opens with a double whammy of Racing Thoughts and Letters from the War Front. The first covers the consumerism of the 1980s with Jeff Koons’ “New Hoover Convertibles, Green, Blue,” “New Hoover Convertibles, Green,” and “Blue Doubledecker.” Also Nam June Paik’s “V-yramid”, a forty television and video assemblage, and Richard Prince’s “Spiritual America,” the disturbing nude image of a ten year old Brooke Shields. The second chapter focuses on the subject of the AIDS epidemic featuring works by David Moffett accusing President Reagan of inaction, Sue Coe’s warning of the proximity of the threat and David Armstrong’s haunting image of his boyfriend.

Distracting Distance showcases ‘newmedia’ artists. One of the Whitney’s favored artists, Cory Arcangel is here with his “Super Mario Clouds,” which is interestingly curated with cables and game systems strewn across the floor. I listened to Christopher Lew, a curator expertly explaining Josh Kline’s “Cost of Living” which is a janitor’s cart carrying items created on a 3D printer.

It is here that the spirit of Gertrude Vanderbilt lives on, trusting these young artists to create works for the museum unhindered, following their artistic instincts. It is a guiding principle that Scott Rothkopf, the newly promoted Chief Curator, will hopefully be able to sustain. It’s not perfect. There are some wrinkles in both the building and the exhibition. The ticket lines are long, the elevators slow and the staircases are narrow causing congestion even at quiet times. The current exhibition floors are difficult to navigate with the numerous chapters laid out haphazardly to the uninitiated visitor with bottlenecks throughout. However overall it is a wonderful new venue and the exhibition is really worth seeing.

Trying to see everything in one visit however is to risk visual, mental and emotional indigestion and utter exhaustion. I recommend several visits if at all possible. Make time to visit the outdoor sculptures, perhaps have a quick bite to eat in the café and if you’re lucky, sit in the armchairs at the West end of the 5th floor under the wall painting by Jonathan Borofsky “Running People.” You won’t regret it.

Whitney Museum of American Art