John Emmett Connors has been making art for most of his 72 years; his inspired efforts vary with his life experiences. He grew up in Lansingburgh, a historic village near Troy, NY. Mentored by artist and teacher Robert Beverly Hale, he studied on a scholarship at The Art Students League and learned Japanese Sumi-e painting in both the United States and Japan to enhance his creative process. From both his time with the armed services and his work for years in critical caregiving, he adds a substantial gravitas to his emotional renderings of life’s light and shadows. Throughout the years, he has exhibited in the Albany capital region and in New York City and has published three books about his work.

In 1968 he was called up for military service and enlisted in the Navy Hospital Corps and for a few intense years, performed life-saving work with the sick and wounded and then later, was a helicopter medic with a Marine Corps flight squadron. Privy to both life and death up close, he learned lessons about the human condition although he did not actually fight in Vietnam’s jungles. A great benefit for him at that time was his access to four years’ education on the G.I. Bill studying at The Arts Students League in New York along with his discovery of gay life.

When AIDS reared its horrific head, his commitment to caring deepened and led to a series of art works and a one man show, entitled, “Death and the Celebration of Life.” A few years later, he received a request from Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post to care for a dying relative and became a guardian for a model at The Art Students League. Over time, requests for his ministrations increased with the average case lasting 6 or 7 years. The last person he worked with was Larry Kramer, the seminal AIDS activist, during the final years of his life.

He emphasizes “the care of another human being is a profound responsibility and cannot help but add humanity to your art. The life of an artist can be, almost needs to be, ego-centered and my work as a caregiver has kept me grounded and provided a balance to my life” so he sees both activities as complementary. For him, “the trick is to not get burned out and to reserve enough time and energy to make and explore art,” viewing his military training as helpful.

Making art, he surely did, and his involvement with humanity has always been the subject of his work. He finds “love, hate, death, joy, suffering, sadness, politics, and sex,” can be expressed in a variety of ways, “abstractly, figuratively, or intellectually” and are often intimately felt. For him, the struggle and journey are “to find your voice, your way to express your experience of the world.”

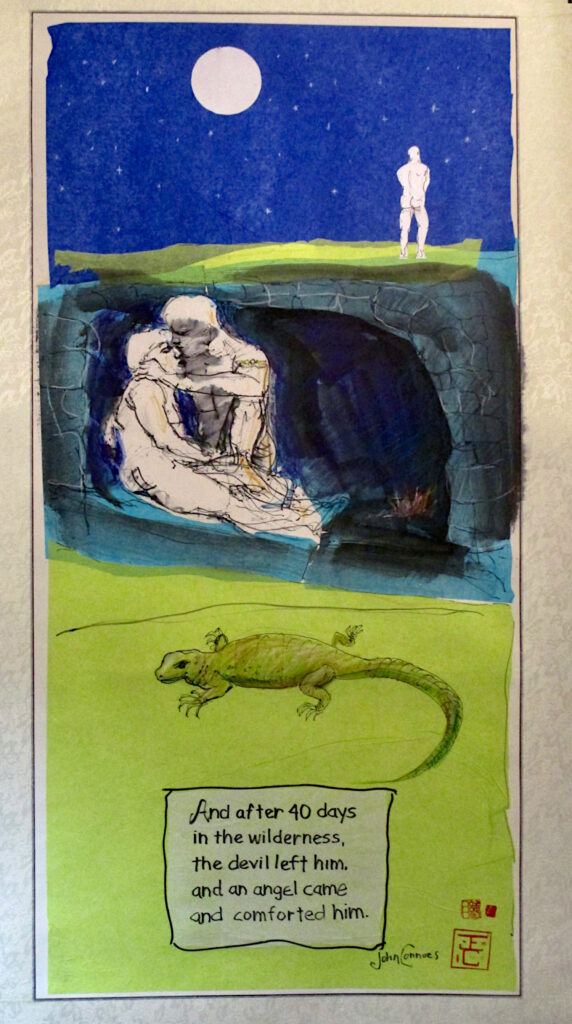

He offers that he is thrilled with what he is doing now, a series of scroll paintings. Several are biblical narratives, others are personal. After his study of Japanese ink painting, “he wanted to speak a more modernist language than what the traditional brushstrokes provided, collaging thin sheets of color tissue paper to get large areas of brilliant color, incorporating both traditional figurative expression and perspective with areas of flat textured color.” Today, his artistic process allows him to work large and the scrolls can be easily rolled up, stored and transported. The pieces do not have to be framed so there is an immediacy to the work, stirring viewer visceral reactions.

John Emmett Connor’s intense pieces caress profundity and compel our truthful responses to his sobering creativity. His interpretations of life’s seriousness help us better understand our actions so we, too, after seeing his art, can assign significant meanings in our own lives. G&S

Leave a Comment