Say the name Jordan Schnitzer to anyone living in the Pacific Northwest region, and they will immediately tell you that—in addition to being a magnanimous philanthropist—he is one of America’s leading art collectors. One of the locations at which he regularly displays his vast catalogue is the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at Portland State University (where art majors in the BFA and MFA programs at the University act as hosts and explainers).

The Museum’s Fall Semester 2024 show—called “Color Outside the Lines”—presents the work of 18 artists and sculptors who have explored the significance and meaning of the use of color in the Arts. The exhibit focuses on whether color in general—or the use of certain colors in particular—has been linked to groups that have faced discrimination within mainstream society. The show considers whether women, people of color, the queer community, and other often-marginalized groups have employed color both as a tool for challenging so-called “established norms” within the art world and as a means to break through stereotypes in society at large.

Several works in the show stand out.

The Korean American artist Lauren Hana Chai (b. 1991) has produced a series of paintings and silkscreens titled Souls in Motion, which are based on her experimentation with DMT—a psychedelic substance found in a variety of plants—as well as her love of Korean folk art and Hieronymus Bosch’s enormous triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (completed in 1510). The show presents the second work in her series, dating from 2020 and measuring 4.5 by 5.3 feet. It is painted with oils and acrylics in dazzling neon colors that—when seen under black light—truly pop off the canvas. Whereas Bosch’s masterpiece is concerned with sin and punishment—a common theme in Catholic-dominated Medieval and Renaissance Europe—Chai explores love, redemption, and acceptance especially though queer relationships—a topic that can still cause rancor in conservative Asian-American families and society. Chai’s depiction of same-sex couples in a vast landscape filled with symbols of Pacific societies is both a tour de force of color and an affirmation of all human relationships.

Equally powerful is Christopher Myers’ (b. 1974) enormous appliqué tapestry—it measures 10-by-19 feet—titled A Story Falls Into the Ocean. It has two inspirations. One is the Senegalese film Touki Bouki, which follows the story of two young adults trying to leave Senegal to discover the mysterious charm of Paris. The images in the tapestry depict characters and scenes from the film. The other stimulus is the Black community in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, and their remarkable quilts that were originally made by enslaved people from scraps of old clothes and cottonseed bags. During the Civil Rights era, the quilters of Gee’s Bend formed a cooperative that sold their work as a symbol of resistance. Thus, the rich colors and design of Myers’ tapestry are a testament to both the history and the spirit of Black culture, whether it is in Africa or the Deep South.

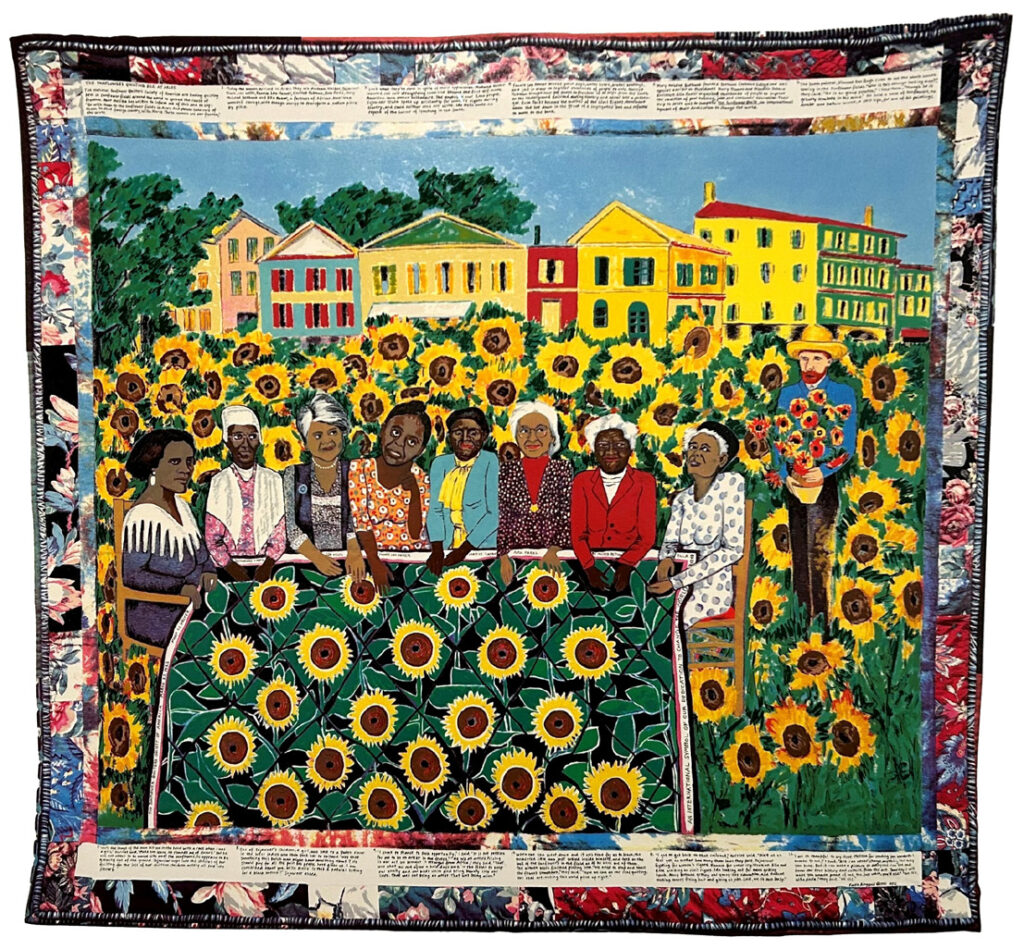

Continuing with the theme of quilts, we have Faith Ringgold (1930—2024) whose various quilt projects span over six decades of her remarkable 93-year life; indeed, they remain some of her best known works. The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles is a 28-by-30 inch silkscreen from 1997 (Edition 205/425) based on one of her larger quilts from a 1990s series called “The French Collection.” This sequence follows a fictitious Black artist named Willia Marie Simone who leaves Harlem and travels to Paris in the 1920s. Over the course of her journey to find her true voice in a more Black-friendly culture, she encounters diverse historical characters—in this particular case figures like Sojourner Truth, Ida Wells, Rosa Parks, and Ella Baker all of whom sit in a field of sunflowers working on a quilt. The sly humor of the piece is found in how the women barely acknowledge the presence of Vincent van Gogh who stands off to the side like some young man being ignored at the school dance.

The use of historical figures and events can also be found in the work of Isaka Shamsud-Din (b. 1940). He is an artist, educator, and civil rights activist known in the Pacific Northwest (especially Portland, Oregon) for his rich murals, paintings, and community projects that celebrate the Black community and the often forgotten figures of African-American culture. Jesse Stahl and the Gun Slinger (completed in 2005) is a 70-inch tondo (round painting) that portrays a legendary cowboy and rodeo rider of the early 1900s. Stahl was one of the great bronco riders of his era and despite his appeal with both Black and White audiences, he rarely won a first prize because of his race. In this work, the horse and rider are set in the midst of a brilliantly colored flaming background that at once depicts the energy of the moment as well as the inner rage that many onlookers may have felt when Stahl was denied top honors.

Also juxtaposing bold colors is Stanley Whitney (b. 1946), but the energy in his work is quite different from that found in the pieces by Shamsud-Din or Myers. As a young man in the 1960s, Whitney was sometimes shunned by other Black artists who felt he should be creating a specifically “Black Art” that reflected the struggles of the community. Whitney ignored the pressure of groups like the Black Panthers and remained true to his commitment to abstract art. By the mid-1990s, Whitney had discovered his signature “block style,” which is on display in this show through an untitled 2007 monotype on handmade paper, which measures 40-by-72 inches. Whitney believes his choice of colors is informed by his culture: “I think there is something about [both] music and color that could be called African-American.” In other words, for Whitney, rather than depicting specific events or persons, he uses color in his bold abstractions that are informed by his experience of being a Black man living in America.

These five artists—and the other 13 represented in the exhibition—explore how the vivid use of color can tell the story of people who have often been neglected not only in the art world, but in the world at large. These inventive creators celebrate the colors intrinsic to their respective cultures through vibrant artistic expression—art that was once dismissed, ridiculed, or purposefully ignored. G&S

sites.google.com/pdx.edu/jsma-at-psu/color-outside-the-lines

Leave a Comment