Probably no other exhibition in recent years is as fascinating and mysterious as “Wangechi Mutu: Intertwined” at the New Museum in New York City. This is the only museum that is dedicated to introducing new art and new ideas by artists who have not yet received significant exposure or recognition. Mutu’s major solo exhibition brings together more than 100 of her works—painting, collage, drawing, sculpture and film. The entire museum is devoted to the Kenyan-born artist’s huge range of work from the 1990’s to the present.

Starting with the seventh floor Sky Room, a luminous penthouse space with glass walls, surrounded by a terrace, you enter Mutu’s art-inflected world and never leave it as you wander through the entire museum from floor to floor. Mutu has created a woman’s world in which she explores decades-long legacies of colonialism, globalization, while evoking African folklore and cultural traditions.

In the Sky Room, Shavasana 1 (2019), a cast-bronze sculpture of a woman’s body sprawled beneath a textured palm blanket dominates the room. It is the perfect place to begin an exploration of Mutu’s work. Shavasana is a death position in yoga and the sculpture was inspired by a Black woman’s murder in California. We don’t see the woman, just her outstretched arms, but as in so much of Mutu’s work, even in death, a sense of life emerges. The dying woman has kicked off one of her high-heeled, lipstick red stilettos. As co-curator Margot Norton writes in her interview with Mutu in the show’s catalog: “There is so much power in your Shavasana works. Though it is anti-monumental to have a figure lying down on the earth, it can be extraordinary powerful.”

“I’m interested in powerful images that strike chords embedded deep in the reservoirs of our unconscious.”

Another equally powerful bronze sculpture is Crocodylus (2020), which refashions a picture of the supermodel Naomi Campbell riding a crocodile. It evokes the tradition of African folklore which often refers to hybrid beings. For Westerners, unfamiliar with the folk tales of Africa, so many of Mutu’s works remind us of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where gender is fluid, nymphs and humans are transfigured and two bodies melt into a single one “seamless as water.” In an article in the NY Times Mutu is quoted as saying: “My point really is to try to use visual art, historical language, and images and objects to flesh out a more African-centric history that predated colonization.”

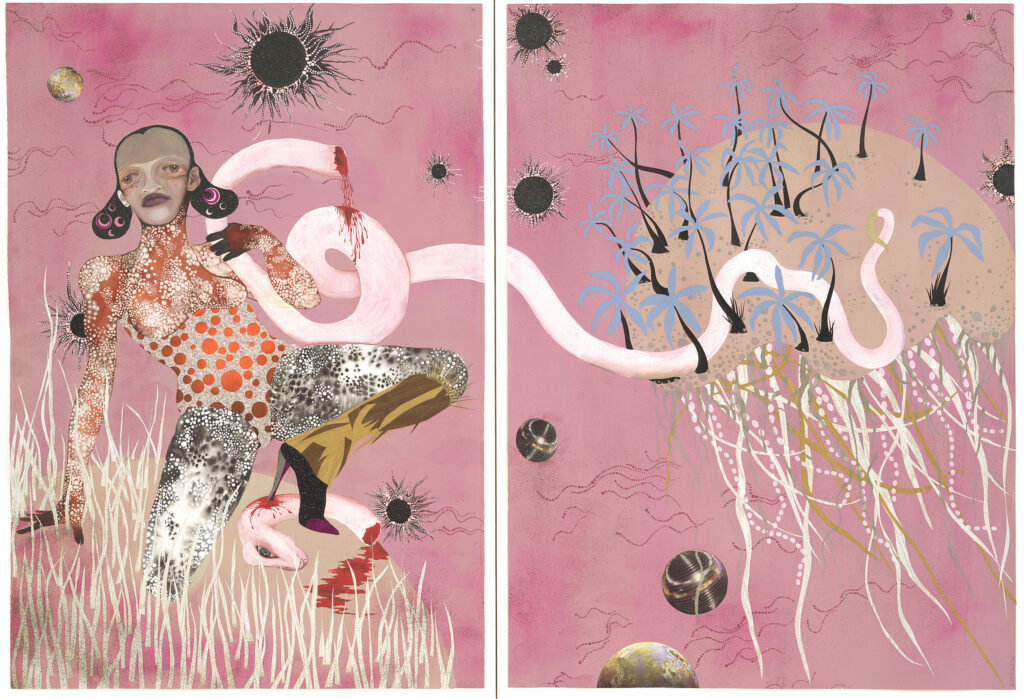

Mutu’s Yo Mama is a diptych (2003), collage-based work that confronts the stereotype of Black feminine weakness. It is a tribute to Funmilayo Anikulapo-Kuti, the mother of the famous Afrobeat musician Fela Kuti, and a pioneering feminist who is thought to have been the first woman in Nigeria to drive a car and who fought for women’s health issues. Mutu depicts her as a Biblical Eve, slinging a headless serpent across her shoulder while (yes, another high-heel) stiletto boot mutilates the snake. This diptych is an outstanding example of layered references (a snake caused the downfall of Eve). The artist has said: “I’m interested in powerful images that strike chords embedded deep in the reservoirs of our unconscious.”

Mutu usually is the star of her own videos. In one shown on a broad screen, she portrays a woman balancing a heavy basket on her head as she struggles up a hill. Locusts and birds harass her but she continues, growing smaller as her burden metamorphosizes into a slithery blob as it goes over the edge of a cliff.

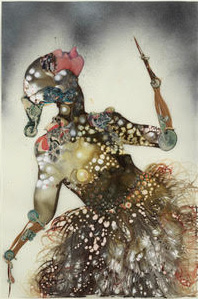

“Dancer,” 2004. Ink, acrylic, spray paint, and collage on mylar 36″ x 24″. Collection of Ellen Stern, in loving memory of Jerome Stern. Courtesy of the artist.

Mutu, who is represented in most of the major museums worldwide, is best known for her collages. There are many examples in this exhibition, all surrealist with mismatched faces and distorted images.

Born in Kenya in 1972, Mutu was encouraged by her parents to draw as much as possible. She went to boarding school in Wales, attended the Parsons School of Design, Cooper Union and received a master of fine arts degree from Yale in 2000. Today, she lives mostly in Nairobi but also has a studio in Brooklyn.

NY Times writer Roberta Smith writes that this exhibition reveals Mutu to be “one of the best artists of her generation, using her innate versatility to demonstrate diversity as essential to life, real or imagined.”

Wangechi Mutu’s vast, inventive work is almost impossible to characterize. There is a grandeur and majesty in all that she does, whether glittery, glamorous,

or earthy clay and wood. Mutu knows no boundaries with her imagination and investigations of violence against women and the environment. G&S

Leave a Comment