by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905)

It wasn’t easy being a woman artist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Yet, through determination and a healthy dose of feistiness, Elizabeth Jane Gardner overcame numerous obstacles in a male-dominated system and emerged as one of the most successful American artists of her era. Once all but forgotten, today Gardner is again being recognized as an important figure in the art community of fin de siècle Paris.

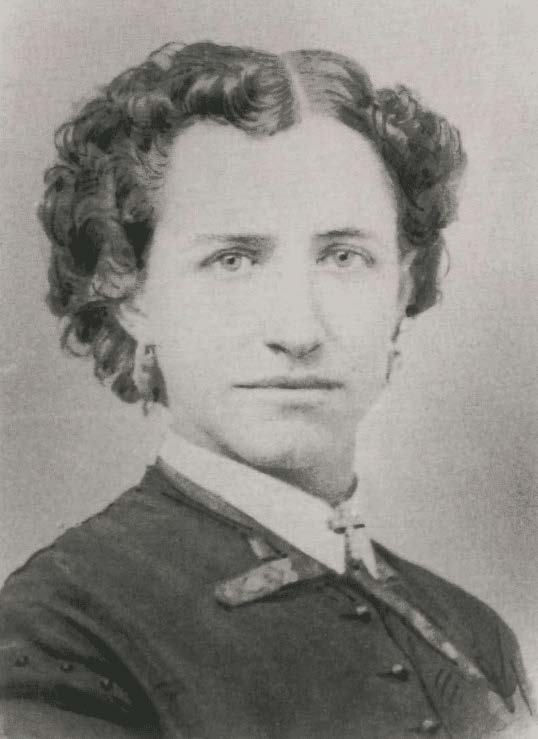

Born in Exeter, New Hampshire in 1837, Gardner always showed a proclivity towards art and languages. After attending several all-women’s academies in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, she taught French and art from 1856 until 1864 when she and a former art teacher —Imogene Robinson— left for France.

To pay the rent on her flat, she spent her days copying paintings by contemporary artists as well as the Old Masters that were displayed in prominent Parisian galleries. In short order, Gardner’s small studio became a place where visiting Americans and others commissioned copies of their favorite European paintings. Because she was fluent in English, French, Italian, and German, she was able to build great rapport with a variety of clients and she was never without work. She once wrote to her brother John: “One gentleman was so satisfied with a copy I did for him that he paid me more than I asked.”

But Gardner also began producing a large body of original work, and by 1868, the 31-year-old artist was the first American woman to exhibit at the internationally famous Paris Salon. Indeed, she would end up showing her work at 25 Salons over the years and in 1887 became the only American woman ever to receive a medal at the Salon. Of course, all of this is ironic when you consider that she was denied entry as a student into the École des Beaux-Arts, the most prestigious art school in France. The school would eventually change its admissions policy in 1897, 35 years after Gardner had initially applied.

But Gardner was a very determined woman. She studied privately and —like her contemporary Rosa Bonheur— received a police permit allowing her to wear men’s clothing in order to attend life drawing classes that included male nude models. Finally, in 1873, she was admitted into the previously all-male Académie Julian where she studied with William-Adolphe Bouguereau, one of the most famous French artists of his day.

After only a few months, Bouguereau, who was 12 years older than Gardner and already married with children, began a rather steamy affair with the younger artist —and for the next 17 years they carried on a very open and sometimes scandalous relationship. As the years slipped by, Bouguereau’s wife and four of his five children died. His mother made him swear that he would never re-marry, so Gardner and he refrained from formalizing their relationship. However, when dear maman passed in 1896, the couple lost no time getting married, and they lived quite happily until his death in 1905. Gardner would go on to live another 17 years, passing away in 1922 at the age of 85. Over the years, Gardner began to develop a style that was nearly indistinguishable from that of her husband’s, something for which she was sometimes criticized.

Indeed, at one point she said to a friend: “I know I am censured for not more boldly asserting my individuality, but I would rather be known as the best imitator of Bouguereau than be nobody!” That’s a fascinating statement, isn’t it? First, it tells us of the fame of her husband. He was well-known and prolific, leaving behind over 822 known canvases by the time of his death. Yet the statement also tells us something of the relationship she had with him. Was Gardner’s artistic imitation the result of some kind of co-dependent fiasco or was she so comfortable with his style that she found it the most conducive to her various subjects? Whatever the case, Gardner produced some truly beautiful work.

Probably her most well-known work in her lifetime was her monumental The Shepherd David, completed in 1895. That year, she wrote her sister Marie that the 3.5 by 5 foot painting would soon grace a full page in the art dealer Albert Goupil’s publication listing the best pictures of the year. (You may remember Goupil as the employer of both Theo and Vincent Van Gogh.) Today this extraordinarily detailed work is on display at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC.

Currently on loan to the Portland Art Museum, is another remarkable work called Le Captive. Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1883, the nearly 4 by 6 foot canvas is typical of Gardner in that it depicts an anecdotal scene in a timeless, bucolic world. The captive of the title is the white dove, which traditionally symbolizes love, purity, and peace. But at the time, it also was generally understood as alluding to the loss of innocence—both sexually and psychologically. The mystery presented in the painting is whether the dove is being removed from its cage or being put back in; there appears to be a tension between the two women regarding that issue. (As an interesting side-note, Gardner kept an aviary in her studio, so it’s quite probable that the dove depicted in her painting was her pet.)

Another beautifully crafted painting is La Confidence painted around 1880. This 4 by 6 foot piece shows a whispered secret shared by two peasant girls. The painting was given to the Lucy Cobb Institute, an all-girls school in Athens, Georgia. It hung in the drawing room parlor of the school for years and was seen as having a “moralizing purpose” for the young girls enrolled in the finishing school. Today the work is on display at the Georgia Museum of Art on the campus of the University of Georgia.

If you do a quick search of Gardner on the internet or in art books, the most frequent word you see to describe her is “academic.” At one time that term —academic painter— was pejorative. Today, academic painters like Elizabeth Jane Gardner are being thoughtfully reconsidered as master craftspersons who anticipate, among other things, the emergence of photorealism in later 20th century art. And Gardner was a master —her use of light, her meticulous brush strokes, her accomplished sense of composition are exemplary. To study her is to learn about the circle of women in Paris —which included Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, and Louise Breslau among others— who were truly trailblazers, who fought —and often succeeded— in upending the chauvinistic “boys club” of the late 19th century art world. G&S

Dr. Bill Thierfelder, Ph.D. – Arts and Humanities makingwings.net

Leave a Comment