Tweet

Like

Be the first of your friends to like this.

Remember the house where you grew up? Not the awful one. The wonderful one. It could have been your own house or apartment. Your aunt’s, your best friend’s, or somewhere you stayed with your family on a trip.

Wherever it was, it has to have been some place that awakened a spark in you: A dream. A longing. An urge to remember and to possess.

My friend Ed grew up on New York City’s Lower East Side. His neighborhood was a hodgepodge of immigrant groups. Mostly Irish, Jewish, and Italian. He came from a burly, two-fisted clan that measured masculinity by the six-pack and condemned anyone interested in the arts as being unmanly and effete.

But Ed loved to draw. He loved to read. And he loved to visit his friend’s apartment, because it was filled with books. Books piled high on shelves like offerings to deities of the intellect. Books in an atmosphere that somehow helped a boy who had not lived among them to grow up and conquer the world they represented.

My late husband, Charlie, told me stories about his family’s summerhouse on Long Island. He spoke of riding his bicycle. Mile after mile after mile. Of fishing off the pier and waiting for his father to return from his city job so that Charlie could proudly display his weekly catch. He spoke of hedges grown so high the neighbors complained. Of the freedom and joy of being a child. And when he spoke, I could see in Charlie’s gorgeous, diamond blue eyes, his house, his yard, and his cherished memories of being immortal and young.

I grew up in a suburb of Chicago. My father was an entrepreneur, a landlord, and an inventor. My mother was his aide de camp and all-purpose doer of everything else. He taught us how to dream. She taught us how to implement those dreams.

We lived in a big Tudor house that, if I tried to invent a setting for a family of seven, could not have been more perfect. We had a music room with Spanish tiles and a mahogany Steinway baby grand. There were diamond lead glass windows in our living room that reflected flames crackling in the fireplace, and there was a wonderful kitchen with cabinets that, in a moment of whimsy, my mother had painted alternating shades of white and pink. My sister Selma had her own bedroom. It had purple walls. It also had an attached bathroom that she didn’t have to share, with purple tiles, a purple sink and even a purple tub. Our parents’ master bedroom also had a private bath. And a dressing room, like in an old Cary Grant-Myrna Loy movie. Linda and I shared the bedroom with the pink butterfly wallpaper; and my brothers, Mikey and Chucky, slept in the room with the built-in bookshelves. It was from their window that I used to spy on Selma and her boyfriend when they swung back and forth in a hammock strung between two pear trees.

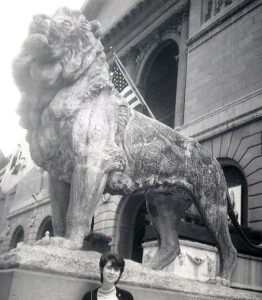

The Art Institute on Michigan Boulevard was my other home. My father had a lifetime membership there, so that is where we waited for him after we visited the dentist, before our ballet lessons, and whenever he was busy doing this or that. It had big, well-lighted galleries displaying Monet’s haystacks, Picasso’s Guernica, Seurat’s Sunday in the Park, Breton’s Song of the Lark, and the Thorne Miniature Rooms. My favorite place in The Art Institute, however, was not at an exhibit. It was in a niche behind an obscure wall on the first floor.

There, lined in plush red velvet and studded with brass, was an honest to goodness treasure chest. Like the one marked by a big black X on Long John Silver’s map of Treasure Island. I would gaze, transfixed, through the brass grid that covered bright copper pennies, shiny dimes, quarters, and silver dollars, and I would fantasize about glittering diamonds, blood red rubies, and gold doubloons. A discrete sign above the treasure chest advised that all contributions went to The Art Institute School, but I never believed it. I knew that the treasure chest was there for me. To look at. To dream about. To bolster my belief that somewhere in the real world, there existed thrilling adventures worthy of the life I fully intended to live.

I have been back to the town where I grew up many times. During each visit, I could easily have knocked on the door of that wonderful old Tudor house, told its current owners who I was, and asked if they would be willing to give me a tour – for old times sake.

But I never have. I never will.

As long as I remain outside, my old bedroom will still be papered with pink butterflies; the bed in Selma’s room will still be covered with a ruffled purple spread; Mikey and Chucky will still be whispering boy-talk across from their built in bookshelves; and my father will still be sitting with crayons and scissors at my mother’s dressing table, making us magical cardboard cages which revealed a brightly colored parrot if you pulled the cage bars to the left or a snarling orange tiger if you pulled the bars to the right.

It is the same for The Art Institute in Chicago. I have been back there often, too. Guernia has not been exhibited over the stairs to the basement for many years; the Monets, Bretons, and Seurats are a little harder to find; the Thorne Rooms have been refurbished and restored. And the treasure chest is gone, gone, gone. Last time I visited, it had been replaced by an ugly Plexiglas box.

But when I think about that wonderful old Tudor house … when I think about The Art Institute, Charlie’s carefree Long Island summers, or the apartment of Ed’s bookish friend, I realize that they are not really gone, and that nothing can really replace them. They will exist as long as we do.

Forever unchanged. On permanent exhibit. In the Museum of our Minds.